The topic is as evergreen as the Christmas trees decorating our homes these days.

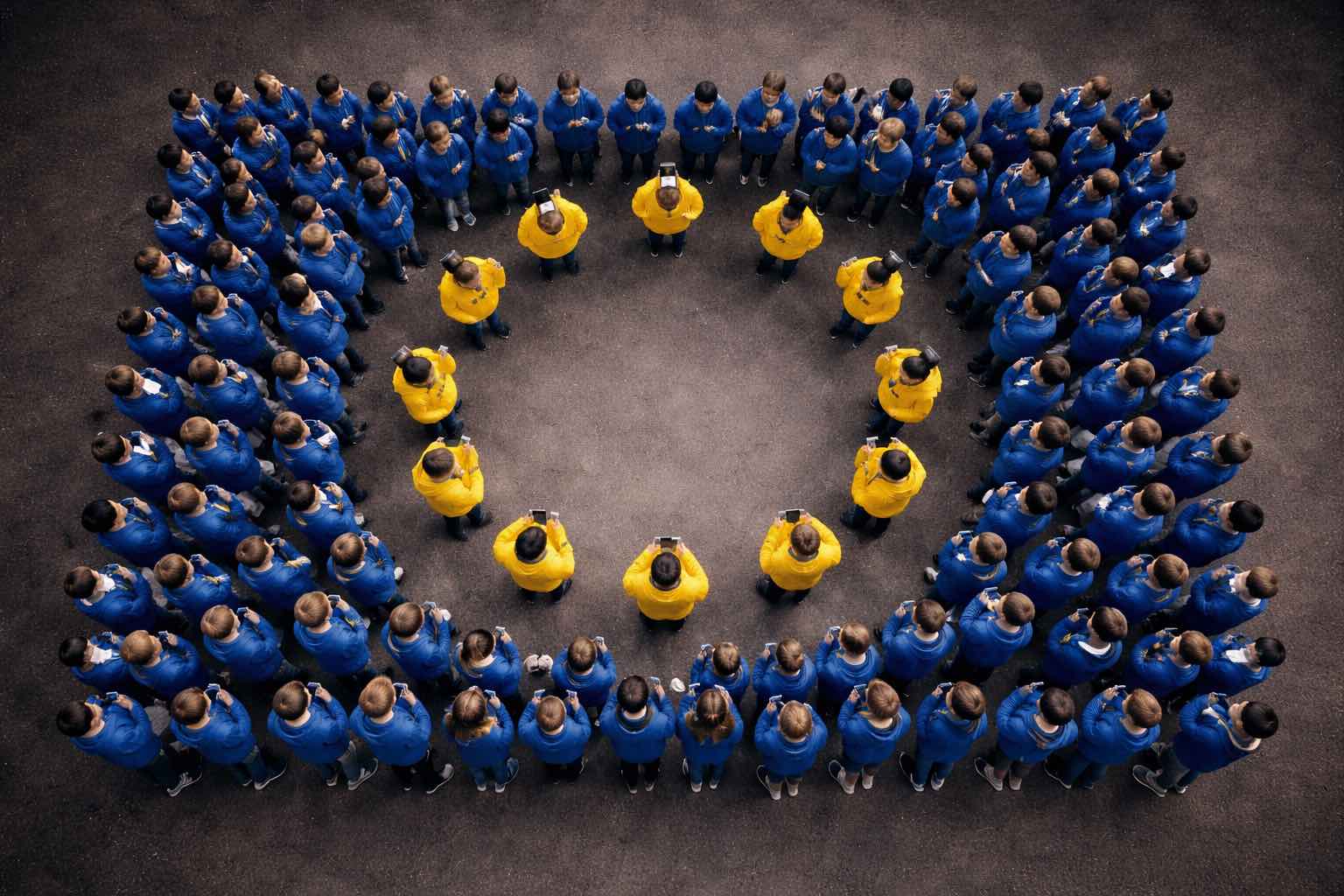

Yet, when it comes to regulating social media, governments and institutions are moving at a snail’s pace, despite the overwhelming scientific evidence.

The issue is pressing.

How to protect our children from the harmful influence of social media.

One year, two democracies with two markedly different answers.

In Canberra, the parliament amended the Online Safety Act on December 10; and set a national minimum age. Platforms must take reasonable steps to prevent Australians under 16 from holding accounts.

In Brussels, after many rounds of consultations and negotiations, the European Parliament adopted a forceful but non-binding resolution. With vastly different content.

When Australia decided that children under sixteen should not be on social media, it did something unfashionable from European perspective: it decided, based on facts, research and clear perspectives, then transformed it into legislation.

In their understanding, it’s the companies’ algorithms that are responsible for the problem (children getting harmed because the platforms are optimized for engagement), thus the companies can and should use the same algorithms to solve it. To avoid privacy issues generated by different age verification schemes, Australia requires ‘reasonable alternatives’ from companies without institutionalizing invasive identity surveillance.

Children should and would not be punished, only the companies if they try to play the rules and allow teens to stay on platforms.

Parents should and would not be involved, because the focus is on lifting social and peer pressure in one moment to make detachment easier.

The European Union chose a different path.

All the debates lead to no real solution, just questionable directives to enhance parental control and combine those with digital ID applications.

Greece, for example, has adopted an age-verification and parental-control application called Kids Wallet that parents use to monitor, block or allow access to social media for minors. It links to the national digital identity system and lets parents enforce restrictions on devices. Under this scheme, social media access for under-15s in Greece is restricted: children must have parental permission — with the app acting as the enforcement mechanism.

The strategy is framed as parental empowerment and protective monitoring, not a platform mandate like Australia’s law.

Experts warn that requiring ‘parental policing’ will only lead to family conflicts and increased social exclusion, ‘empirical social-science cautions that turning parents into the primary enforcers risks unequal protection, family conflict and the social exclusion of children who are kept offline while their peers remain connected’.

Peer pressure remains and parents will eventually lose the battle. The real winners will be the social media platforms that can build ginormous data bases.

Systemic regulation alleviates this burden without building ‘identity factories’.

Instead, the EU decided to push for a path with much higher additional risks – probably in fear of the major platforms, it decided to hide behind fancy sounding declarations evoking human rights, such as ‘children are not merely vulnerable subjects but autonomous right holders’.

The institution so eager to regulate everything from packaging to the size of cucumber, decided to take the easier path and shift the responsibility to the families.

European policymaking has developed a distinctive reflex when confronted with technologically mediated harm.

The reflex is not to prohibit, redesign, or compel the market to change its behavior.

The reflex is to empower—a word that here means transferring responsibility downward until it lands safely inside the living room, between the couch and the Wi‑Fi router.

Thus, the emerging European approach to children and social media: parental regimes, age-verification wallets, device-level blocking tools, and earnest reminders that mothers and fathers must take the bad cop’s role in this battle. In a battle where top platforms’ hundreds of behavior scientists and their algorithms are against average people and developing average teens.

What could be go wrong?

One of the more revealing aspects of the European debate is not what it includes, but what it systematically ignores. Adolescents do not make social-media decisions in isolation. They make them in groups. Peer presence is not a secondary factor; it is the engine. Most impressively, it assumes that if one fourteen-year-old is banned from Instagram while her entire class remains online, the problem will politely solve itself.

Social pressure is what turns optional participation into compulsory membership, especially among teens. It is what transforms ‘you don’t have to be on this app’ into ‘you don’t exist unless you are …. or .. you are the creepy one who is not online’.

Any regulatory model that leaves participation uneven—permitted in some households, forbidden in others—does not reduce pressure. It concentrates it in a disgustingly hypocrite way.

Australia understood this intuitively. By making the rule general, it removed the stigma of individual abstention. No one had to be the only child without an account. No parent had to become the villain of the household. The policy did not merely restrict access; it normalized absence.

Europe, by contrast, has chosen the artisanal approach and added some extra spice to family conflicts of European households. Every family is invited to handcraft its own regulatory regime. Some will block. Some will negotiate. Some will surrender quietly.

Under the ‘moralizing’ European model, platforms retain their most valuable asset: plausible deniability.

They can express support for child safety while quietly continuing to optimize for engagement, virality, and behavioral capture. If underage users remain on their services, it is not because the system invited them, nudged them, or profited from them. It is because a parent somewhere failed to toggle the correct setting.

It would be unfair to say that Europe is doing nothing.

Europe is doing what it does best.

It is harmonizing discussions. It is issuing resolutions. It is commissioning studies. It is preparing future frameworks that will one day enable action, provided consensus can be achieved once.

In the meantime, children remain online.