In the pharmaceutical industry, human experiments are heavily regulated, with built-in safeguard measures and a lot of public scrutiny in place.

In light of the recent investigations of the Dutch news outlet Zembla, governments and city halls are apparently not under the same constrains as the ‘big pharma’.

It wasn’t a human experiment, per se. But for all practicalities, it was.

The City of Amsterdam started a brave integration project in 2018.

Codenamed Stek Oost, it was a temporary housing project, based on a utopian idea.

Authorities moved so called status holders (refugees with residence permits) and Dutch students into one housing unit. The project was run by Socius Wonen, a housing NGO.

The aim was to promote integration and community.

Well-meaning officials at the Gemeente Amsterdam (city hall), had probably imagined students and refugees sitting together, teaching each other crafts, and spending long nights around a bonfire singing pop songs.

The reality is more harrowing.

According to Zembla’s investigation, many residents, especially young women reported repeated sexual intimidation, harassment, assault. Living conditions were deemed unsafe, supervision was non-existent.

It’s up to further investigation why it took authorities six years to react.

People interviewed by the outlet claimed that they were afraid to speak up.

That, in the idealistic liberal world of inclusion and tolerance, they feared that they are going to be labelled ‘racist’ or ‘overreacting’.

That, when they did speak up, management claimed that it was ‘cultural misunderstanding’. Or worse, raised their hands defensively and told the residents to ‘solve it themselves’.

Structural mismanagement was prevalent, worsened by low investment and the notion that it was all ‘temporary’.

Independent oversight could have solved some of these issues, drawing attention to safety, mental health, or to the lack of staff with necessary qualifications. It could have called for more social workers, psychologist or experts who could have pointed out that cultural differences, especially around questions like gender, privacy, relationships and personal boundaries, should not be underestimated.

But the truth is Amsterdam desperately wanted the project to succeed – thus complaints were deemed politically sensitive and swept under the rug.

It could have been a symbol of integration and innovation, combined with affordable housing.

A success story following many failed integration attempts.

Sweden’s ‘Etableringsboenden’. Germany’s Willkommenszentren. France’s Centres d’Hébergement d’Urgence. Belgium’s Zamenhuizen. Or another Dutch project called Startblok Riekerhaven.

All started with the same concept: mixing young people with refugees.

It sounds simple on paper.

Let’s mix groups and they’ll learn from each other.

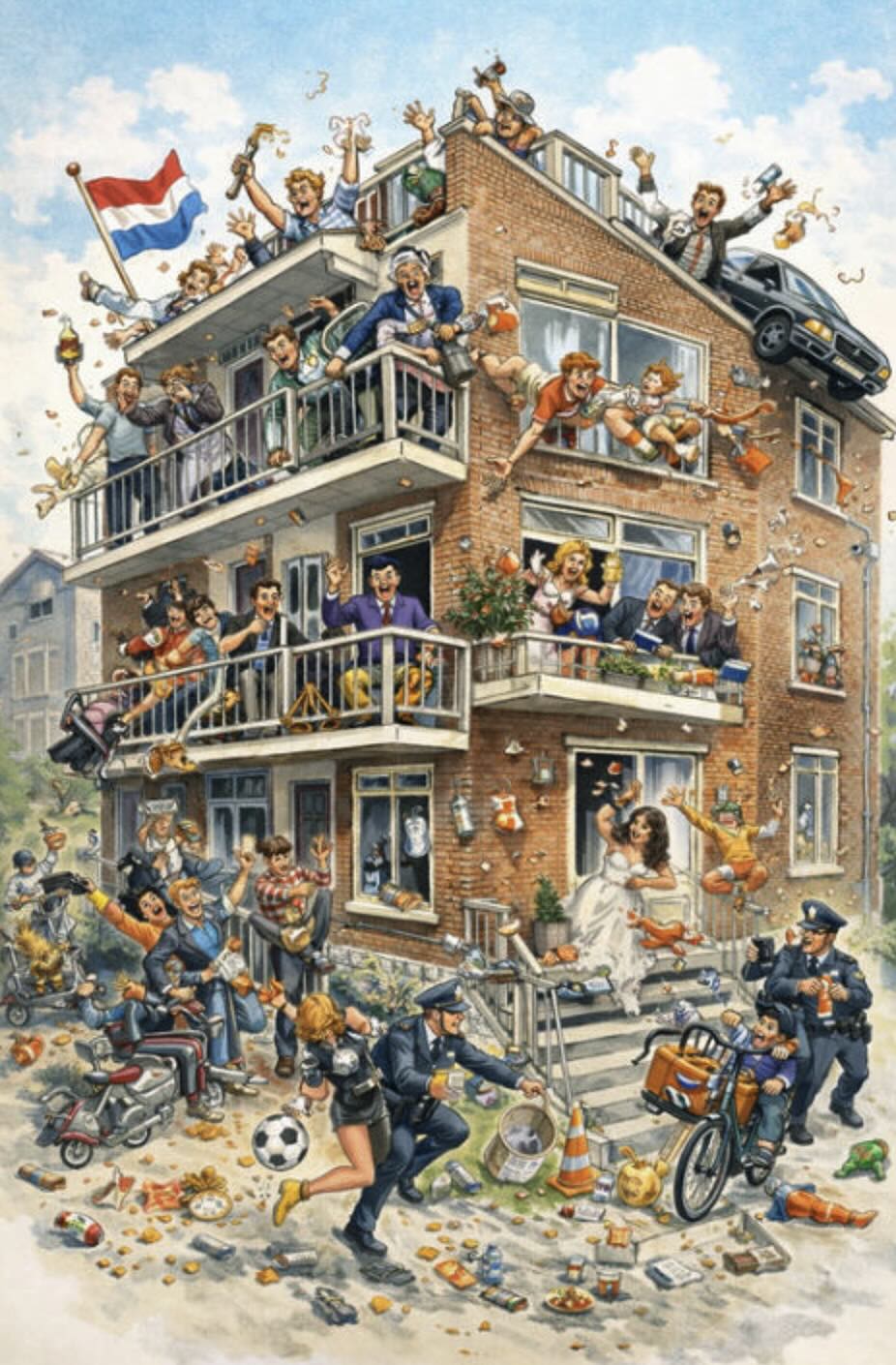

The outcome was always Lord of the Flies in real life: no rules, no supervision, no conflict-resolution, and no authority to turn to. A world in which power dynamics formed naturally – homo homini lupus est. The strongest or more desperate won.

And when the problems surfaced, authorities reacted like Golding’s naval officer, ‘I should have thought that you can put up a better show’.

Between refugees from war-torn countries and inexperienced European teens, the outcome is, or at least should have been to anyone with a basic level of survival instinct and a touch of realism, unambiguous.

At the start of these projects, idealism was stronger than realism.

Then reality fought back.