If there would be a competition for the most boring and predictable press moment, the one during the visit of President Xi to Paris would be a contender for the top position.

Probably nobody expected grandiose declarations or the announcement of billion dollars’ worth of investments, but even after the visit is over, not much is known about what the three leaders (Xi, Macron and von der Leyen) talked about.

Very likely because of the precarious situation Europe’s leading economies found themselves in the last couple of years. In cases like this, less publicity might be more desirable.

Just a few months ago, the EU’s Executive Vice President, Valdis Dombrovskis, stressed the importance of not severing ties with China while also advocating for protective measures against unfair practices. Ursula von der Leyen echoed similar sentiments recently, albeit with different phrasing. Messages not completely in line with Washington’s expectations.

Though not admitted openly to the public, but for the well-informed politicians of Europe, it must have become evident by now that Europe lags behind China in many aspects.

The Old Continent is unable to compete with Chinese speed.

This, on the other hand necessitates a few tough decisions to buy time for the EU without completely disengaging from China, a crucial market. Especially not so right after the EU’s separation from Russia. While in the coming months and years, Europe plans to erect trade and investment barriers to counter China, for the time being policymakers are (hopefully) aiming to strike a balance between competing objectives to reach a mutually acceptable outcome.

The problem has been the same for quite a while: Europe hasn’t been able to develop a comprehensive strategy to compete with the Chinese economy (or at least copy the US Inflation Reduction Act).

It is true that EU-China relations have taken a plunge “thanks to” Beijing’s support to Russia in the Ukraine conflict. But the process has been an ongoing one as Europe has been trying to reduce its dependency on China (at the pressure from Washington, to a great extent).

A not really successful effort.

Ironically, in spite of the tough rhetoric, the sad reality is that the EU’s dependency on China has exponentially grown in the last years. And not just for “rare earth materials” or “as an export market” or “the most important industrial partner in green transition”.

The “average European” may not be aware of the fact that China’s economy and research and development prowess have undergone a significant transformation over the past twenty or fifteen years. Europeans have long been accustomed to associating Chinese industry with cheap and low-quality goods. People are often overlooking the broader scope of China’s industrial output.

Beyond the “copycat era”, a new phase of Chinese research and development is emerging, characterized by substantial yet still cost-effective production capabilities, abundant human and mineral resources, and comparatively fewer environmental regulations. These are mainly just dreams of any European industry.

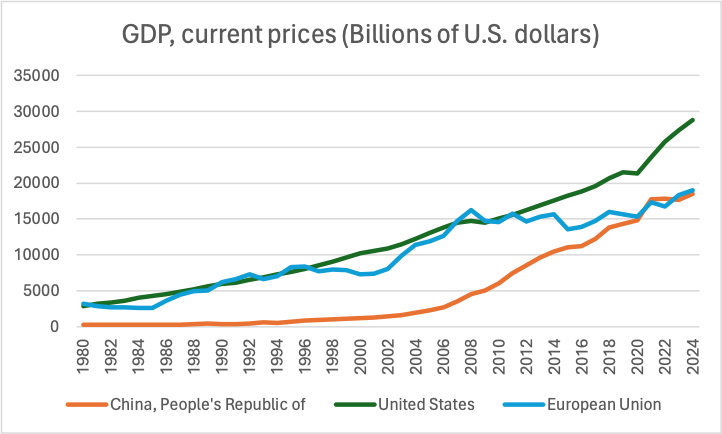

To illustrate how China’s evolving capabilities have driven changes, we can refer to the statistics provided by the IMF.

In 2000 the Chinese GDP based on PPP was only 7.2 percent of the global output and the EU had 20.2 percent. In 2023, China had 18.73 and the EU 14.45 percent, respectively.

The picture is slightly distorted, of course: based on the total GDP (and not on purchasing power parity), the US economy is still stronger than the Chinese.

Unfortunately, the outlook for the EU is drearier. The EU’s GDP is still higher (with a hair’s breadth), but the trend is clear, that China and the US are growing, while the EU is struggling.

The contrast is even more obvious if we look at two key sectors of Europe’s much hoped for Green Transition: solar panels and electric vehicles.

European solar panel producers follow the debate with some desperation: around 95 percent of the existing European solar capacity is based on Chinese solar panels. While Brussels still only scrambles to establish itself as a global player in clean technologies, Beijing and Washington poured hundreds of billions of state subsidies into their green industries. In comparison, European manufacturers started layoffs this year or have asked for EU support to avoid closing factories. Some are relocating to the US, like solar panel producer Meyer Burger that is packing up a German factory to send production to the United States.

If anything, this trend shows a complete failure of European politics on the field of the one of the fastest growing industries, in a moment when the expectation is a yearly 20-25 percent growth of solar capacities. A dream strongly supported by EU funds, much to the delight of Chinese manufacturers.

On the field of electric vehicles, the situation is not that bad, but far from great.

As a laudable development, new electric car registrations reached nearly 2.4 million in 2023 in the EU, increasing by almost 20 percent relative to 2022. (In comparison: China saw the biggest increase with 8.1 million, and the USA was the third with 1.4 million cars)

But the good news mostly end here: despite the very famous and strong European car manufacturers, about 19.5 percent of all electric cars sold across the EU were built in China. If we take Germany out of the picture, the result is even worse: in France and Spain close to every third EV sold in 2023 was made in China.

Presently, more than half of the “Made in China” vehicles were produced by Western carmakers: 28 percent of all made EVs were imported by Tesla, with Renault’s Dacia adding a further percent. But Chinese homegrown brands are quickly catching up: from 0.4 percent of the EV market in 2019 to 7.9 percent in 2023. According to the estimations, this number will grow for 25 percent this year. Even more worryingly, Chinese companies are clearly ahead of Europeans in terms of battery technology and supply change readiness. Once an unimaginable scenario, today a very realistic future, but it might be Chinese companies who will bring new RD and technologies to Europe and not the other way around.

Yes.

Another not-often advertised change is that but China and Chinese researchers have started to be ahead in several fields.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute (a defence and strategic policy think tank based in Canberra, founded by the Australian government, a country more focused on China than anybody else in developed world and one that probably understands the “dragon” more than the rest, too) published an interesting research last year, comparing the most cited research outputs in critical technologies.

The report was based on the analysis of the top 10 percent of the most highly cited research publications released between 2018 and 2022 in 44 technology sectors, ranging from artificial intelligence to advanced robotics and quantum computing. And defence and space-related technologies, not to mention advanced aircraft engines, including hypersonic technology.

Probably shockingly, China leads in 37 out of 44 Critical Technology Sectors, while “Western democracies are losing the global technological competition, including the race for scientific and research breakthroughs, and the ability to retain global talent”.

After China and US, India and UK lead the smaller group, which also includes South Korea, Germany, Australia, Italy and Japan. There wasn’t a sector in which European countries would have occupied the first or second places. Among the first five countries Germany appeared 24 times, Italy 14 times, France 5 times and the Netherlands 2 times. But there are 29 sectors, in which there aren’t EU members among the top five.

In 15 sectors the Chinese presence is so high that the technical dominance is unquestionable. For some technologies, all of the world’s top 10 leading research institutions are based in China and “are collectively generating nine times more high-impact research papers than the second-ranked country (most often the US)”.

China has changed in many ways.

The short and long term implications of this are manyfold, but it is very likely that China’s position within the global supply of certain critical technologies will grow exponentially in the future, further eroding the dominance of the US.

It is up to Europe to choose between Scylla and Charybdis. Or maybe try to navigate its rhetorical ship in between the two.