Dark suit. Dark tie. Grim face. Solemn, slightly dramatic voice.

As if on a funeral.

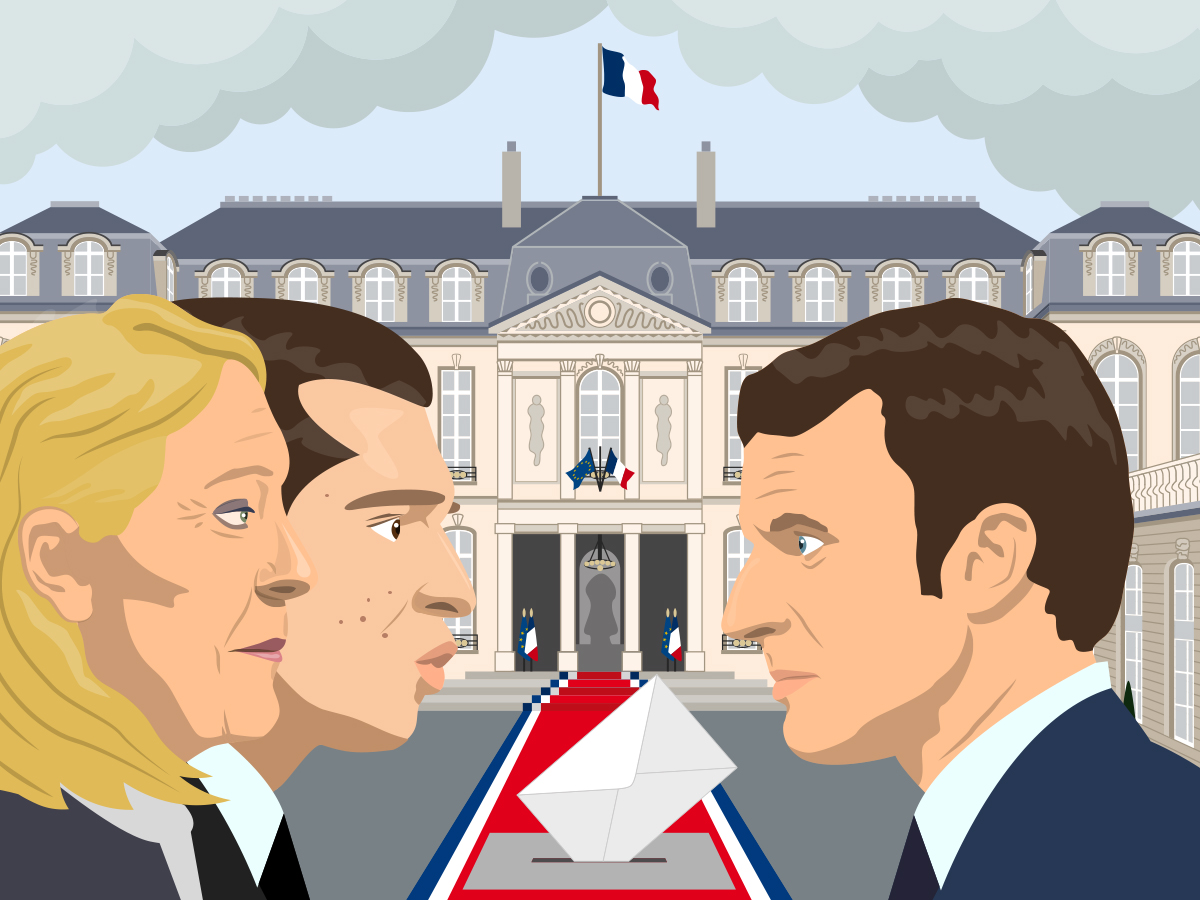

This was the image French President Emmanuel Macron projected when he declared that “I’ve decided to give you back the choice of our parliamentary future through the vote”, then announced the dissolution of the parliament and called for snap elections on June 30.

Dissolving the “Assemblée” was originally meant to ensure that no incompatibility between the president and the parliamentary majority blocks the functioning of the state. But with a little twisting of the interpretations, it is now used to get a “clear view”, or as Macron put it, to “clarify” the country’s political landscape.

To measure the real support for the (far-)right or, maybe, to show that the Ensemble/Renaissance has not completely lost the faith of the population, no matter how bad it fared on the European elections. (No wonder he warned voters to reject extremes and embrace his coalition.)

Currently, the Rassemblement National (RN) is measured somewhere between 29.5 and 35 percent, the Nouveau Front Populaire (the left) at 22-28.5 percent, while the Les Républicains between 6.5 and 9 percent.

It is Macron’s Ensemble/Renaissance which is measured on a much wider range by the different polling agencies (though each point at slightly higher support than what was shown on June 9). Elabe, Cluster17 and Ifop/LeFigaro all put them at 18 percent. At the other end of the spectrum is Opinionway that shows 29 percent support.

On the other hand, in the highly volatile and rapidly changing environment, polls might “expire” faster than normally.

Macron’s surprise step set enormous powers in motion (and stopped others, as all current legislative projects have been suspended, pending review in the next legislature, if and when the new government decides so). All can alter the landscape any day.

Parties on all ends of the political spectrum are scrambling to form electoral alliances in the brief time at their disposal.

Surprisingly, the left side of the spectrum proved better at forming alliances. On June 13, the Socialists, the France Unbowed Party, the Greens and the Communists announced a common platform (Nouveau Front Populaire). They also agreed to eliminate competing candidacies and to perform a “total break” with Macron policies. Former president Francois Hollande was quick to endorse the new grouping.

On the other hand, the “mainstream right”, France’s traditional conservatives (Les Républicains) are in turmoil. Party leader Eric Ciotti was expelled (twice, actually) after forging an electoral alliance with RN – only to have the decision suspended by a court. A win (even if a temporary one, maybe) for Ciotti, who declared the effort to be “quibbles, little battles by mediocre people … who understand nothing about what’s going on in the country”. He might have been right on that, at least based on the dismal electoral results of his party.

The Les Républicains might be divided over the issue of cooperation with the far-right, but the important thing is that considerable part of the membership is open to that. As prospective MEP Francois-Xavier Bellamy worded it, he “would of course vote for an RN candidate over the left in a second-round run-off. I’ll do everything to prevent La France Insoumise from coming to power”.

A win for RN.

In fact, Marine Le Pen was quick to promise a “unity government”, would her party win the elections, to “pull France out of the rut”. On June 10, party leader Jordan Bardella “stretched out his hand” both to the “other” far-right party, Reconquete!, and to the conservative Les Républicains (though the latter were not completely content with the offer, as the soap opera of Ciotti’s expulsion proves it).

Jordan Bardella is taking the elections seriously. On June 18, he asked the voters to give nothing less but absolute majority to the party. “I need an absolute majority”, he told reporters, “I don’t want to be the president’s assistant”.

As for the centre, Macron can only hope that his grouping will not fare worse than on the European elections. The central message of the campaign is being the single alternative between “the plague and cholera”, as Francois Bayrou (Macron’s ally) described the left and right.

Macron won a second term a little more than two years ago (April 2022). Per the Constitution, nobody can legally force him to leave, no matter how he struggles to keep the voters who elected him in 2017, not to mention his inability to gain more support. Thus, he will be the head of France for three more years.

That much is granted.

Alas, even if he bet right and his Ensemble/Renaissance comes out from the snap elections slightly better than from the European “contest”, they will have to find a way to work with a stronger than ever opposition.

But (what seems now more likely), if the RN will win the elections, Macron might spend the next three years “in cohabitation” with Marine Le Pen and Jordan Bardella. Or at least one year before he can dissolve the National Assembly again.

An interesting situation at best.

Cohabitation means a more secondary role for the president, as not even foreign affairs and national defence are his exclusive domains.

Something Macron is not used to (most French presidents are not, especially not since 2000, when the transition to a five-year term and the change in the electoral calendar made “cohabitation” hypothetical, as the president has always easily won a majority in the Assemblée Nationale merely a few weeks after his own election).

The last time a French president decided to dissolve the National Assembly (Jacques Chirac in 1997, trying to strengthen his majority), the step backfired and the left won 38.05 percent of the vote and 255 seats – and instead of a strong majority, Chirac “gained” a fragile situation and often borderline paralyzed cooperation.

Would Macron and Le Pen be “forced” into cohabitation, they should come to a mutual understanding on Ukraine, Russia, China or Green Transition. Something highly unlikely, rendering constant friction unavoidable.

That, of course, could play to Macron’s hands with time. Jordan Bardella might have been right when he said that if voters “place the country in a situation of relative majority, we could not change things”. A year spent with constant battles might stall a few reforms in France, but can easily erode support for RN, as well.

Unfortunately, a weak France today is not just a domestic problem. Especially not with another lame duck sitting in Berlin.

In two weeks, the world will see whether it was a calculated risk taken by a politician who has not much to lose (but more to win) or Russian roulette played with Europe.