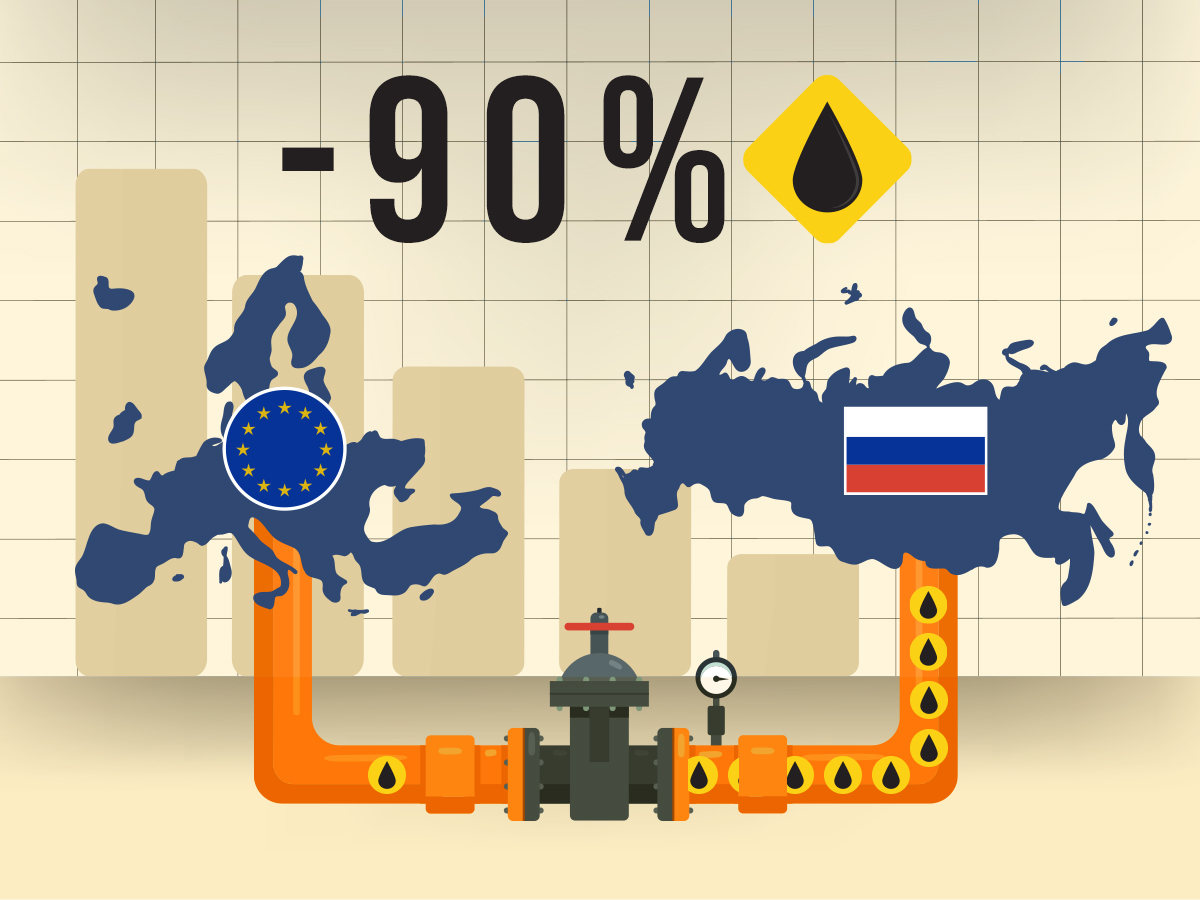

After a few weeks spent with intense debates, the leaders of the EU finally managed to reach an agreement on the sixth sanctions package against Russia; arriving to a “you can have your cake and eat it too” solution, enabling Hungary (and other, less-vocal but very similarly dependent countries like Slovakia, Bulgaria or the Czech Republic) to keep on buying oil from Russia, while agreeing to halt 90 percent of all Russian oil imports by the end of the year.

The result would be, according to Charles Michel, a relatively quick ban of about 70 percent of all Russian oil exports to the EU, with an additional 20 percent cut off by the end of 2022. By all estimates, this would cut off a large source of financing for the Russian war machine, as about two-thirds of that oil arrives by sea.

The ban technically exempts all oil arriving via pipelines, so if and when they’d need it, Germany and Poland could also withdraw their voluntary pledges to stop buying Russian oil. And while most leaders vowed that the exemptions were temporary or would be taken up “again at the very next summit”, as Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte had promised it, they were necessary to proceed.

The EU had to reach an agreement in order to maintain the united front against Russia, or as Charles Michel put it, “I think that more than ever, it’s important to show that we are able to be strong, that we are able to be firm, that we are able to be tough in order to be able to defend our values, to defend our interests”.

One important lesson learned during the process was that next time (during the negotiations about the seventh package, that, in theory, would include some form of ban on Russian natural gas), first it would probably be better to talk about the actual technical details and only after that announce the sanctions, rather than doing it in reverse and desperately try to find a commonly acceptable solution in the aftermath.

The lesson could be perhaps applied to other upcoming negotiations, as well.

The issue of the ban on Russian oil was a pressing, but; unfortunately, not the only pressing issue the EU faces, as the several phone calls during the last few days between leading politicians from all over Europe and Russian President Vladimir Putin had shown it.

The problem in question is the export of Ukrainian wheat (and sunflower oil).

Probably understandably, the Russian president didn’t really feel forced to give concessions amidst the Russian army’s slow but solid advances in the Dombas region (especially the assault on the Ukrainian city of Severodonetsk) and amidst the ever-growing fears of a global food crisis; no matter how many times he was asked to do so during the 80-minute call with French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz.

As Russian forces seem to have made some progress in achieving the re-evaluated goals for the “special military operation”; and it is also unlikely that the event described by President Zelenskyy as the probable prerequisite to Russia’s participation in peace talks (a.k.a. Ukrainian forces recapturing all the territory that was lost since February 24) would happen soon, with or without NATO delivering all the weapons systems requested by Ukraine; Moscow doesn’t feel the sense of urgency.

On the contrary, Putin reportedly warned both leaders of the dire consequences of an eventual delivery of heavy weaponry, claiming that it risked “further destabilizing of the situation”. A clear message after the repeated Ukrainian requests for US-made long-range multiple-rocket launchers; something yet to be delivered, but (at least according to US officials) under “active consideration”, after the delivery of M109 howitzers.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan wasn’t much more successful in his quest to find a solution to the crisis, even though before his own phone call with his Russian counterpart, he expressed his optimism that “the war between Russia and Ukraine will end in peace as soon as possible”. He told President Putin that Ankara was ready to take on a role in an “observation mechanism” between Russia, Ukraine and the United Nations, would such an agreement reached. He also urged Russia to take confidence-building steps to end the conflict.

The two leaders also addressed maritime security in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, also talking about the issue of de-mining the waters, bilateral trade and, of course, the possibility of opening a safe passage for Ukrainian wheat.

All three leaders urged Putin to lift the Russian blockade of the port of Odessa, to allow Ukrainian grain exports. Russia reportedly showed openness to do so (Putin was quoted saying that he “wants to allow the export of grain from Ukraine, especially by sea”), but for a heavy price: the lifting of the anti-Russian sanctions.

In Putin’s reading (but at least in his rhetoric), problems with food supplies were caused by the “misguided” Western sanctions, anyways. Russia also offered to increase the quantities of Russian fertilizers and agricultural products, the moment the sanctions would be gone.

The sad reality is that a solution for the export of Ukrainian wheat (and sunflower oil) is urgently needed.

The economy of Ukraine is hurting far more than the Russian, and so do the other European economies. According to the latest data, inflation in the Euro-zone hit a record 8.1 percent this month, the worst since the euro was introduced in 1999. Already high oil prices edged even higher after the announcement of the sixth sanctions package, fueling the cost-of-living-crisis in several states.

Though it is hard to predict, how conflicts end, most experts agree that this specific one is likely to drag on for years, and there is a high likelihood that Russia would try to “lock in” the territory already secured and just like with Crimea, present the world with a fait accompli.

With neither of the parties directly involved in the conflict being ready or feeling forced to make concessions, it is difficult to tell, how the world could access those much-needed commodities, as alternate routes (trains, road transportation) are much costlier and definitely less effective. That can hardly be changed within a short time, no matter how many pledges European leaders have taken to hasten the process.

Olaf Scholz might have been right, when he said in Davos that Vladimir Putin would not win the war in Ukraine, but it is probable that he would not lose it, either, especially not in the short term. This gives Russia a bargaining chip (along with the ever-present threat of nuclear war or the hints at instigating some sort of an uprising in Moldova) that is hard to counter.

Maybe it would be time to calculate the opportunity costs of different decisions.