What to expect from the new German government

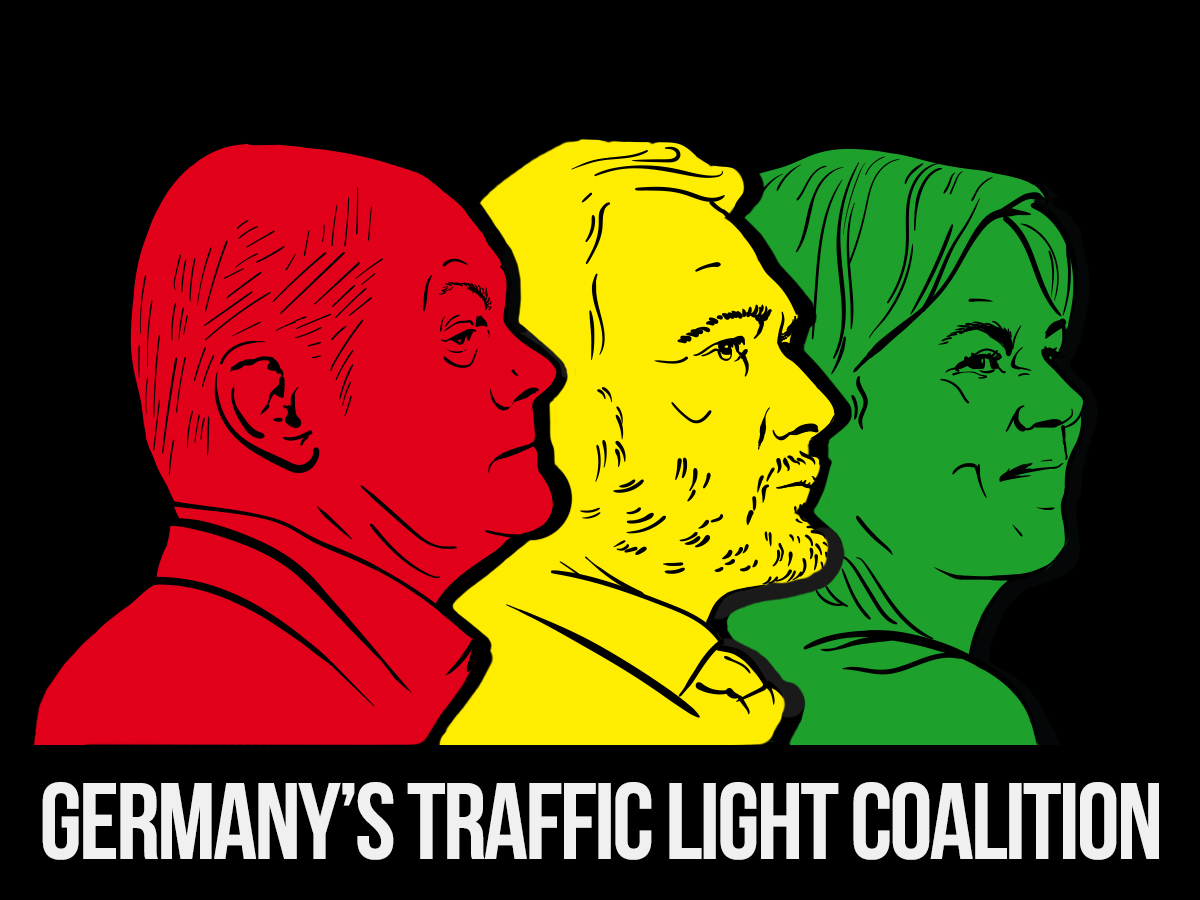

It is not final yet, as it needs to be approved by the parties themselves, but after weeks of negotiations, the coalition agreement is ready for Germany’s Traffic Light Coalition. If everything goes according to plans, Olaf Scholz can be sworn in before Christmas. And then Angela Merkel can finally leave office and enjoy her retirement, after getting her own Großer Zapfenstreich on December 2, listening to Nina Hagen and Hildegard Knef.

Chancellor-hopeful Olaf Scholz was optimistic, despite acknowledging the difficulties the three parties had, “We are united in a belief in progress and that politics can do good. We are united in the will to make the country better, to move it forward and to keep it together.”

Here are a few things one shouldn’t miss about the agreement.

I. It is pretty much like any other coalition agreement

The document, titled Dare to make more progress, is about 178 pages and involves everything from infrastructure to minimal wage.

Some of those policies, especially in the energy sector, will mean a radical departure from the previous 16 years, others will look more like continuance (see foreign policy).

Some promises involved there sound more like wishful thinking than reality, for example the aim to go coal-free by 2030; even if they might be more realistic than the program of the freshly elected Romanian government that dreams about buying hydrogen trains in a country with a notoriously unreliable train system.

Others seem to be contradictory, like all the effort to transform to green economy, raising the minimum wage to €12 and to start or finish long overdue infrastructure projects and the reactivation of the country’s debt brake, a.k.a. the necessity, or even obligation to have a balanced budget, that would make borrowing money extra difficult. Add to this the agreement on not raising taxes and even Albus Dumbledore might not be able to conjure the necessary amount. And the new government won’t only need to find the way to finance investment into green energy projects, it also has to make sure that the population can pay for it, especially since the country already has one of the highest electricity prices of the continent.

2. Just like with most government plans, it depends on outside factors

The incoming government faces some internal challenges, like the fact that some ministries that might have colliding agendas (see in Point 1) are in the hands of coalition partners with opposing worldviews, like the finances in the hands of the FDP, and the climate-energy-economy ministry in the hands of the Greens. Managing day-to-day affairs might easily turn into a balancing act for Mr. Scholz, who himself is more of a status-quo type of guy, campaigning with the buzzword “continuity”.

But there are also many factors, Mr. Scholz has little-to-none control over.

Among the outside factors faced by the new government are known knowns, like the Bundesrat, where the CDU/CSU still can build a majority, unknow knowns, like how the next wave of the COVID-19 or how exactly the currently experienced glitches in global supply chains will impact the German economy and unknown unknowns, or let’s call them Black Swan Events if you prefer, things we can’t even think about now. Those not only might derail the most well-intentioned plans, but might also undermine the coalition itself. Even for unknown knowns, it is nearly impossible to prepare, not even with setting up a “federal-state crisis team and group of experts”.

3. Expect Green activism all around Europe

It might actually be a win-win situation, that the Green’s got the foreign ministry. Besides the fact, that the would-be chancellor is not a man known for his foreign policy ambitions; the office that wasn’t especially important under Merkel still might turn into a useful tool for the Traffic Light Coalition.

With its focus on rule of law and climate change, but also a tougher stance on China (as it is proven by the emphasis given to the one country two systems in Hong Kong principle in the coalition agreement); the MFA can channel “Green” energies away from home, allow the Green Party to show itself and let it’s voice be heard even if things might not go exactly according to plans at the home turf, e.g. the country won’t be able to raise the share of renewable resources from 35 percent to 80 percent within the matter of seven-eight years. It can surely also fight endless wars abroad to achieve “necessary treaty changes” that will “lead developments to a European federal state”.

Financing for such activism might be tricky, though (see point 1.), even if the coalition plans to spend 3 percent of the country’s GDP on foreign action.

The promise of “solid finances and the frugal use of taxpayers’ money” might collide with Green plans to support green transition in other countries and might also signal some dark days ahead for countries affected more severely by the pandemic, that benefited from the laxer German approach to fiscal policy in the last two years, even if the agreement only states that “EU-fiscal rules need to be developed further” and should be “simpler and more transparent”.

Also, the fact that the Nord Stream II pipeline is not even mentioned in the document, might question the extent to what the three partners managed to agree on it. But the ostrich-policy, namely pushing my head into the sand and pretending that the problem doesn’t exist, even if ostriches do not push their heads into the sand; cannot be sustained in the long turn.

Poland has already signaled its hopes that the new government will change its attitude towards Russia in general, and the Nord Stream II in particular, but it is rather unlikely that taking a firm position on the controversial project will be one of the first steps of the coalition. In that, they might turn into the good old “merkeln” tactic, trying to avoid the need to make decisions as long as possible.

The new migration and asylum policy of the coalition might turn into yet another hot potato, both at the home front, where it already got criticism from the opposition, and on the EU level. The parties said that they would seek a fundamental reform to the EU asylum system, with their goal being “to establish a fair distribution of responsibility and jurisdiction for admission of migrants among the EU states”, add to this “effective external border protection based on the rule of law.” This has been an ongoing topic for many years and adding “rule of law” to the mixture might not be the right direction, not to mention the proposed changes in German naturalization and residency procedures, that many claim will turn into “pull-factors” for would be migrants.