From time to time, Facebook (or Meta?) bombards its users with online quizzes, like “Who said this?”, “From which book is this quote?” and alike.

Inspired by it, let’s play a game.

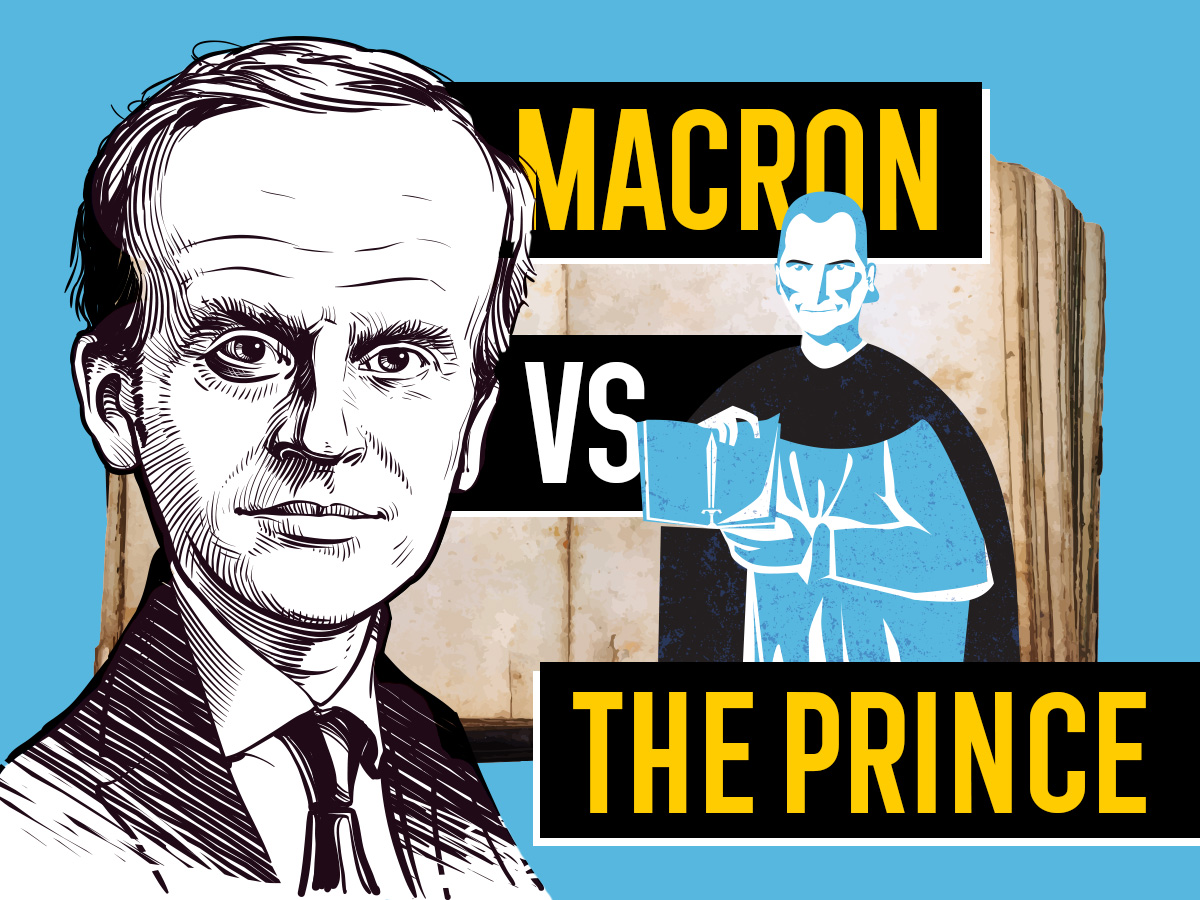

Who said it: Vladimir Putin or Emmanuel Macron?

“… foreign propaganda media are the main drivers behind the spread of disinformation …”

Those, who guessed President Macron were right.

In his new year speech on January 11, he said that online platforms and foreign “propaganda” media were the main drivers behind the spread of disinformation in the country, adding that whatever measures are to be taken, “the same must apply to foreign media authorized to broadcast on French soil”. Then, reflecting to the works of the Enlightenment in the digital age committee, he proposed and outlined a few plans to rein in “foreign media”, emphasizing the necessity of a framework of responsibility.

As the step clearly mirrors Russian (and other illiberal) efforts to control “foreign media agents”, I couldn’t help thinking about a very well-known expression.

The end justifies the means.

Or variously worded versions of it.

From 16th century political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli’s most famous, but also probably most controversial work, Il Principe.

Many, among them Prussia’s Frederick the Great in his Voltaire-enhanced Anti-Machiavel, had questioned or criticized the book’s main ideas, especially the propagation/admission of the use of immoral strategies, but it is undeniable that Machiavelli had a serious effect on modern politics or political theory, especially on political realism, inspiring thinkers and politicians from John Milton through Benjamin Franklin to Adam Smith. (And 20th century Italian-American mobsters, but that’s another story.) Henry Kissinger is said to have had a copy of The Prince on his bedside table, too.

The Enlightenment ideal of kings was that of rational and benevolent statesmanship, in accordance with the movement’s beliefs in the harmony of morality and progress. A noble idea, no question, that looks very good on paper or sounds good in the names of various committees.

But just like Frederick the Great failed to follow his own declarations about how kings should behave (e.g. though he should not have pursued “glory and annexations of territory”, he just did exactly that by occupying Silesia, not to mention the rest), how the planned/proposed French steps will work out will also depend on the outcome of the clash betweeen reality and ideals.

Some forget, that the first country to take a similar step, was the USA, with the FARA act in 1938, to force those representing foreign interests to publicly disclose that fact.

On paper, Russian laws are, not good, but probably acceptable and not much different than the above mentioned American law, requiring outlets and/or individual journalists only to provide detailed financial reports and make it clear with an all-caps warning on their publications, let it be an article or a joke on Twitter, that those were created and/or distributed by a foreign media outlet. (The practice is a different story.)

The stated aim was to make readers/viewers realize/acknowledge that whatever is in front of them might be representing not-necessarily well-meaning (from Russian point of view) foreign interests.

That’s the aim of the French (and American) steps, too; to make French people/European people aware of the fact, that whatever is in front of them might be representing not-necessarily well-meaning (from French/EU point of view) foreign interests.

The only difference is that it is done for the greater good. But that is the level of morals, not politics.

Mr. Macron’s recent statements recalled yet another quote, this time from a Frenchman, a friend of Cardinal Jules Mazarin; “Everyone decries this author [Machiavelli], but everyone follows him in practice, and principally those who decry him.”

Because ideals and political realities not often match (as Machiavelli pointed out by making a distinction between imaginary utopias/ideal republics and real life), leaders sometimes opt to deviate from the noble principles guiding political decision-making.

I’m not arguing for detaching politics for morality or ideals. On the contrary.

I’m arguing for keeping that bond as strong as possible.

But with reciprocating/mirroring the opponents’ steps, one might not exactly be doing that, no matter how “noble” the end seems and how strong the urge is to do something (no matter whether it is good or bad) for the greater good; because it pulls the moral foundation from under the arguments against what is happening elsewhere in the world.

From Russian point of view, they are doing exactly the same, “fighting foreign agents” who are “sowing discord online”; and if they can point out at home that the others in the world are doing it, too, it won’t help truly independent media in the long term.

There are of course, fundamental differences between “state operated troll farms” and “news agencies operating like businesses”, but it is hypocrisy to claim that Western (or any other) media outlets or journalists are always purely and 100 percent objectively reporting and not basing their coverage/interpretation/emphasis at least partially on their own worldviews. (If this would be the case, it would be difficult to explain, how and why so many news agencies can still exist and why FoxNews has a significantly different viewer base than CNN has, for that matter.)

It is weird to see that the country, that has, in the past ferociously defended the freedom of speech, freedom of thought and the freedom of media on many occasions (think about the Muhammad cartoons, when the government declined to ban those based on the freedom of speech principle, claiming that even if some found those blasphemous, the pictures didn’t pass the threshold for incitement to discrimination, hatred or violence), now plans to curb exactly those freedoms.

If the (French) people were trusted to be mature enough to have their own interpretations about that issue (and if that was the case, act within their legal rights against them, e.g. by staging peaceful protests), they probably could also be trusted with deciding whether the French First Lady was transgender (which she is not) or whether believing or not in any other Russian/other disinformation and fake news campaign. Or if Emmanuel Macron doesn’t hold them mature enough now, the question is, why? What political considerations are behind the distinction?

Just like Russian independent media found ways (not necessarily among optimal circumstances, but it’s a different level) to operate despite the “foreign agents law” (e.g. by switching their seats to Latvia), anybody wanting to influence and/or change public opinion will find a way to play restrictions.

If something, educating and sensitizing people about the workings of media, including social media might work better and be more efficient in the long term, maybe would also help the next generations of Europeans outside the world of politics, to stop cyberbullying, online shaming and/or not to fall for recent challenges (think “Blue Whale Challenge”) or hoaxes (“The Russian Sleep Experiment”) on TikTok.