A few weeks ago, China’s attempts to influence research on a Dutch university made it to the headlines, being labelled as “one of Europe’s leading strategic headaches”.

It got revealed that the Free University of Amsterdam got grants for its independent research institute, the Cross-Cultural Human Rights Center, from sources close to the Chinese Communist Party. In fact, in 2018, 2019 and 2020, the center received between €250,000 and €300,000 per year. In a different case, in 2021, a scientist accepted funds from the Chinese state “not to tarnish China’s image”.

The two cases were labelled as a “vulnerability that Europe finds difficult to police”.

Fears of Chinese meddling (and efforts to influence European talk about human rights) are growing.

Well, our parents and grandparents spent a great deal of their lives fearing eggs.

Eggs were often presented as the earthly representatives of devil itself. Based on scientists’ recommendations, cholesterol intake was to be limited to under 300 milligrams a day and not more than three eggs a week.

A few years, maybe decades later, this reference to daily limit was deleted from the guidelines of the American Heart Association, as latest research showed no significant relationship between dietary cholesterol, blood cholesterol and the risk of cardiovascular disease. (Even if the battle over cholesterol is still far from over https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/cholesterol-confusion-and-why-we-should-rethink-our-approach-to-statin-therapy/.)

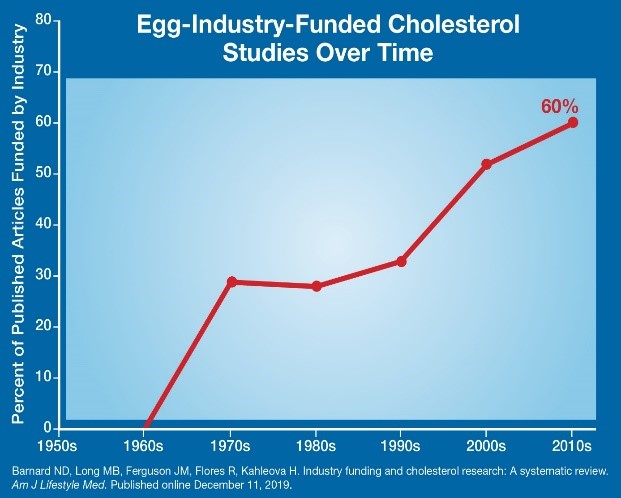

But then came another twist in the story, when, in a series of publications, researchers started to show evidence of industry-manipulated results in 211 studies published between 1950 and 2019. The fresh study (full of colorful charts and infographics) found that egg industry-funded research in the topic was 0 percent in the 1950s, but it was 60 percent of all research during the last decade. (https://urcdn.eu/styles/c5527aa9-d415-408e-85c4-3f180784597c_original?b)

For those, who view the world through a set of pink glasses, it might be a shocking revelation that about half of all the research financed by the egg industry (49 percent, to be precise) was more likely to suggest a neutral-slash-positive correlation between eating eggs and blood cholesterol, despite even their own data suggesting otherwise in a few cases. Research not funded by the egg industry got the same results only in 13 percent of the cases.

The article seems to generously overstep the simple fact that the above result also means that half of the egg-industry-financed research reached different conclusions. Also, it is conveniently silent on where the funding for non-egg industry financed research or the financing of the comparative study itself came from.

Because here comes yet another twist in the story.

The main author of the article comparing those researches happened to be Dr. Neal Barnard, a staunch advocate of vegetarianism, well, more than that, veganism; author of many best-selling books (like 21-Day Weight Loss Kickstart or a cookbook for reversing diabetes) and founder and president of the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM), a 501 (c) (3) organization in the US, defining itself as “a nonprofit organization that promotes preventive medicine, conducts clinical research and encourages higher standards for ethics and effectiveness in education and research”.

Alas, contrary to its name, less than 5 percent of its members are actually people with medical degrees (at least according to a Newsweek fact-finding article), while Dr. Barnard himself is a general physician and not a nutritionist.

The group is at odds with many health charities and/or groups in the US, like the above-mentioned American Heart Association, the American Cancer Society or the Red Cross itself. The group’s links (both personal and financial) to PETA have been shown by many, in fact it was often dubbed as “an animal rights group dressed up as a medical association”.

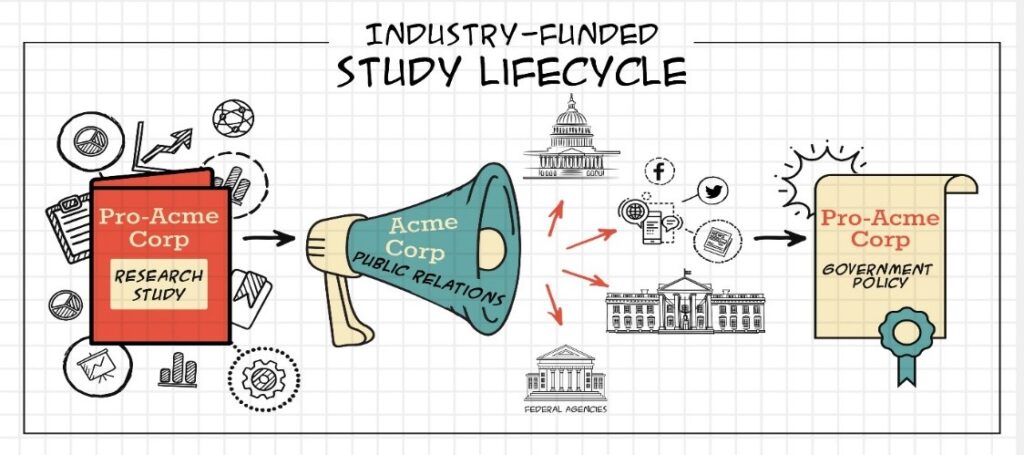

What sets it apart from many similar organizations is that it is consciously and very actively using (social) media and marketing to promote its message. It is not a coincidence, that Barnard’s article on the egg-industry manipulated research results was published and re-published over and over again.

Is it a crime to advocate vegan diet? No.

Is it bad for people? Hard to tell. Surely, there might be many benefits of a more balanced (e.g. less meat heavy) diet, even if scientific evidence on the effects of a purely vegan diet is, let’s say, not that straightforward.

Do they have the right to push for legislation or to sue McDonald’s for feeding people with junk food? Yes, they do. Everybody can push for his or her own agenda and can hope to get more supporters to it. It works somehow like this:

Would the people have the right to know what the real policy behind all those articles and films and advertisements is? Definitely.

Because just like the egg-industry might be imposing its own biases on research, so might PCRM.

People might identify with the results either way (you know the old joke, I’m a vegetarian, not because I love animals, but because I hate plants), but would do it by making a more informed decision.

In fact, in many cases, even with the best intentions and efforts to design objective research, results can be misleading because of unconscious biases (and have no misconceptions, human thinking is wired to be biased in many ways), that influence how a study is set up.

And it is not only eggs.

While there are many advantages of industrially funded academic research, e.g, knowledge transfer, greater efficiency or bigger economic boost, there is a lot of evidence proving that when research was funded by a for-profit and potentially motivated industrial source (think tobacco industry and the Center for Indoor Air Research in the 1990’s, Harvard and the sugar industry in the 1960’s and their “let’s blame fat for heart diseases” campaign or the pharmaceutics industry), this can have potentially negative effects on the openness of science (think non-disclosure agreements preventing the publication of negative results) and can, in fact, diminish public trust in science.

As it was proved by a Pew Reseach Center survey in 2019:

What does this have to do with Chinese funding for Dutch research?

A lot.

The topic or the financer might be different (politics, nations, human rights instead of health and a country instead of a big company) but the underlying principle is the same.

In an ideal world, academic research (or media, for that matter) would be completely independent and would have more than adequate funding with no strings (motivations) attached.

Alas, this is not an ideal world.

And there is a bloody battle being fought for very limited resources. And those limited resources rarely come without at least some strings attached, not even when they come from the EEA/Norway Grants or the Koch Foundation. (Or, like in the case of the German Green Party, from an over-enthusiastic Dutch entrepreneur, who hurried to come forward and declare that he had no interests whatsoever in the Green’s good electoral results, despite his company being heavily involved in green investments.)

Plan B should be more openness (just like the chart above suggests). Namely the funds should be named. Every research, every (nonprofit or research) organization/foundation should disclose where the funding for that particular study came from, probably in a register pretty similar to the one the US has under the Foreign Agent Registration Act.

It would still be a form of exerting “soft power”, yet, at least people would/could make informed decisions.

Just like with media and advertisements, it is hypocrisy to claim foul play when the funds come from somewhere else in the world (let it be China or Russia) and the research financed promotes policies or values contradicting ours; and in the same time, expect those others to allow the dissemination of research promoting our policies or values without exerting some sort of control (e.g. “registering” them as foreign agents”).