There hasn’t been a week lately without an article about the surge of far-right parties in Europe before the next EP election.

If one is to believe the polls, the next EP election will see the dominance of parties that belong to the ECR and ID political groups, while socialists, liberals, and greens are projected to lose a few (many) seats. Again, if experts are right, and the Portuguese elections are some sort of litmus-test, then the results there validate those expectations.

The phenomenon is not surprising, given the continent-wide farmers’ protests, the German strikes, and the economic problems (inflation, rising living costs), etc. etc. Add to this the lingering effects of COVID, the war in Ukraine and the stiffening feeling of uncertainty in the air.

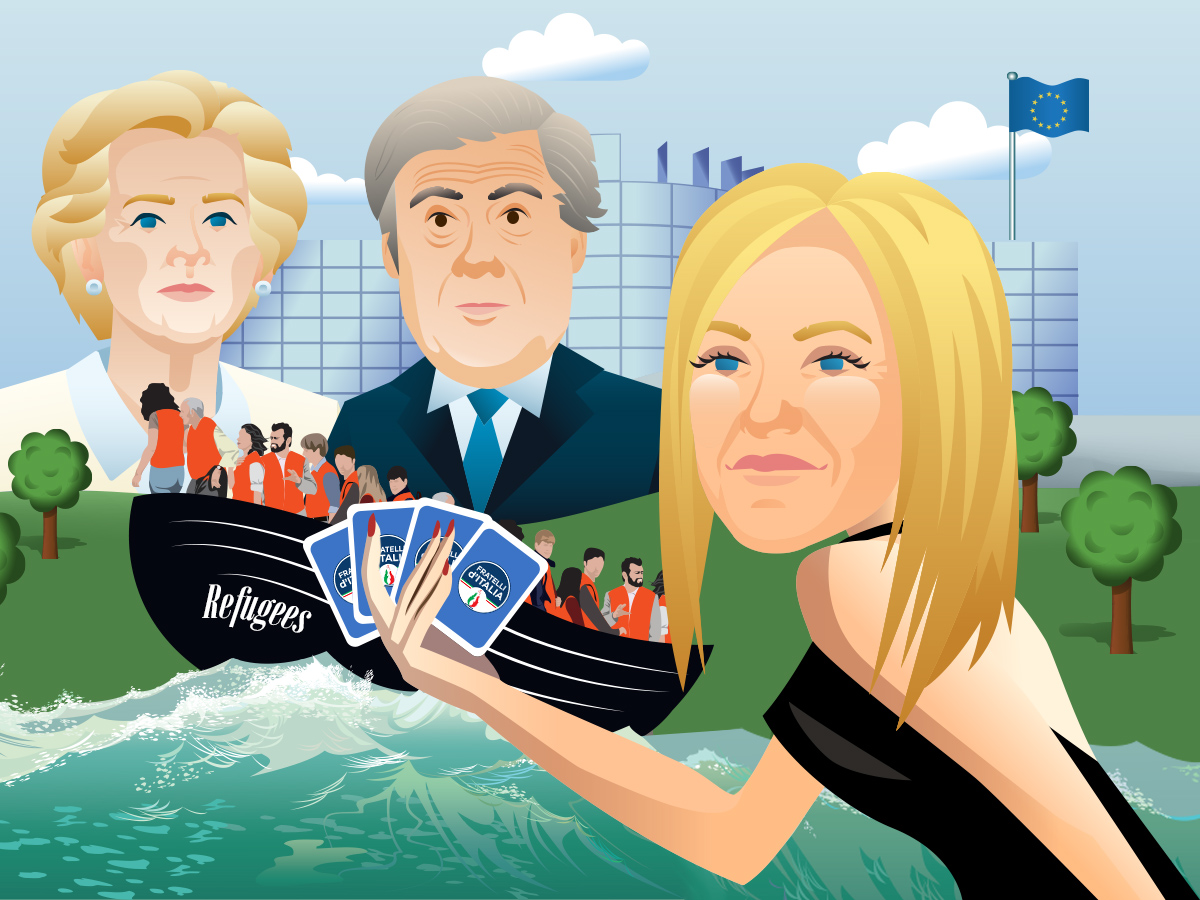

From among the “emerging parties”, much attention was focused on Giorgia Meloni’s right-wing Fratelli d’Italia (now in the ECR). Meloni is not simply the prime minister of Italy (one of the biggest economies in Europe, that could, by the way, produce a 0,9 percent GDP growth in 2023, compared to the Euro Zone average of 0,5 percent), but also a rising star in European politics. Her last two (couple) years marked by one success after the other, a perfect fit into her quick and impressive rise within the ranks of Italian politicians.

Right-winger to the core, Ms. Meloni has been politically active since she was a teenager, starting as an activist in a neo-fascist party’s youth wing in Rome. In 1992, she joined the Youth Front, the youth wing of the Italian Social Movement (MSI), a neo-fascist political party. She later became the national leader of Student Action, the student movement of the National Alliance (AN), a post-fascist party that became the MSI’s legal successor. In 2008, she was appointed Italian Minister of Youth in the fourth Berlusconi government, a role which she held until 2011. She was the youngest minister in postwar Italian political history. In 2012, she co-founded the Brothers of Italy (FdI), a legal successor to AN, and became its president in 2014. In 2020 she was elected president of the ECR. Her party won the September 2022. As the Prime Minister, she has led Italy’s most right-wing government since the war.

Ms. Meloni’s 2022 win (at the end of a brutal campaign) provoked fears in Europe about the ability of a right-wing politician to “fit in” the framework and about the changes in Italy’s positions in the main foreign policy topics. She was quick to promise to govern “for everyone” and has assured Italy’s allies both in NATO and in the European Union that there will be no change in direction in foreign policy. She swore to stand on Ukraine’s side.

Though there were some doubts about her ability to balance Italy’s obligations as NATO/EU member with her support towards the Spanish VOX or Hungary’s FIDESZ party, those proved to be mostly unfounded. In fact, Meloni, using her long-standing relationship with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, played a crucial role in bridging the gap between the EU and Budapest during the debates about the EU’s support to Ukraine. She did it so successfully that many started to call her the “New Merkel”.

Fitting into this new perception was her appearance on European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen (and a few EU leaders) in Egypt. In March 2024, on the occasion of signing a major aid deal with Egypt, worth €7.4 billion. Meloni rushed to hail the agreement as a chance to give “the residents of Africa” a chance “not to emigrate” to Europe.

A virtual “crown” on her career (so far).

Aimed at curbing irregular migration to Europe’s shores and boosting the North African country’s economy, the deal is the proof of her efforts, as Meloni has been a driving force behind such deals. Standing on Ursula von der Leyen side, again (as the president of the Commission has visited Italy several times during the last few months, prompting Nathalie Tocci, the director of the Rome-based Istituto Affari Internazionali think tank to joke that “… she (Leyen) spends more time in Italy than in Brussels these days….”), was the open-declaration of her power to influence the European agenda and do it in one of her most important campaign messages, migration.

Considering her quick rise, the possibility of a political U-turn is difficult to explain.

As the significant surge of right-wing parties seems inevitable, it became obvious that parties on the center-right adapted a new tactic.

Ursula von der Leyen sees Meloni as a solid ally in her bid for re-election, hence, their relationship is getting stronger. At first, it looked as if von der Leyen would accept the support of the ECR for her second term; but later, more and more signs pointed at the possibility of a deeper type of cooperation.

Reports started to emerge that there are efforts to convince Meloni (and her party) to join the EPP instead of merely supporting it from outside.

One clear winner of that change would be Antonio Tajani’s center-right Forza Italia (now in EPP) (and part of the Meloni’s government, as well). Meloni’s EPP membership could strengthen the Italian role within the grouping, in fact, Tajani hopes that he could become more prominent in the EPP (as the older “fish” and prominent member). Indeed, the two Italian parties now have 20 MEPs, that number can grow up to 30 after the next elections (at least according to the polls) and that would make them the most numerous national group. Furthermore, Tajani would win big in domestic politics, too, as accepting a position within the EPP would very likely influence (and do it negatively), Meloni’s stand on the home front.

Ursula von der Leyen in particular, and the EPP in general would also win a lot, especially as the other alternative, getting closer with the Socialists, is not something most (or a significant part) of their voters would necessarily approve. Having a real “right-wing” politician join their ranks would prove their commitment to solve some of the divisive issues crippling Europe. Not so surprisingly, EPP chairman Manfred Weber has also courted Meloni during a series of one-to-one meetings, further fueling the speculation that Meloni might join the conservative group.

Even if nothing materializes from the cooperation after the elections, the prospect in itself might help the EPP, as having a successful right-wing politician appearing on their side might secure some votes from undecided voters. And, alternatively, diminish the chances of Meloni.

Thus, the EPP’s sudden interest is not surprising.

So far, Giorgia Meloni hasn’t revealed her cards.

While the gossips in themselves could hurt her image (making people question her dedication to conservative values, something the EPP has left behind years ago), joining the EPP would bring along even worse consequences, among them losing her “special balancing role” within the ranks of the growing number of Europe’s right-wing politicians.

Instead of being one of the leaders of the ECR, she could easily be pushed back and become a second (third) line politician behind the heavyweights of the EPP (thing Weber). Instead of representing her political agenda and doing it as she sees fit, Meloni and the Fratelli d’Italia would lose their room of maneuver and freedom of action.

So, what’s the deal?