The way we visualize or describe a thing will determine our thinking about the thing itself in the long term. That’s why aspiring journalists and analysts are advised against using too much or too intense adjectives, it might just easily distort the way the reader interprets the story.

The same goes to maps and data visualization.

Cartographers facing the problem of how to visualize a round 3D object on a flat surface came up with many possible solutions. The most commonly used, the Mercator’s projection has its advantages, especially when it comes to navigation (the straight lines and directions helping the users of compasses and GPSs). But one downside is that this method is clearly distorting the size of the landmasses, and thus the countries on them, being shown on a map. And the farther North or South we go from the Equator, the less accurate is the size: that’s why Greenland is shown almost as big as Africa.

Or have you ever wondered how the term the “Far-East” came to being? Well, it’s because how people back then, in the heydays of great discoveries, viewed the world and because, due to this being the dominant worldview ever since, most maps produced have Europe, more precisely longitude 0° in the center. And if Greenwich is the center, then the edges of the map are “far”.

Even though it is not biased or (scientifically) incorrect, it gives us a distorted image of the world. And most people don’t realize that it is distorted.

Things are no different when it comes to mapping the results of elections.

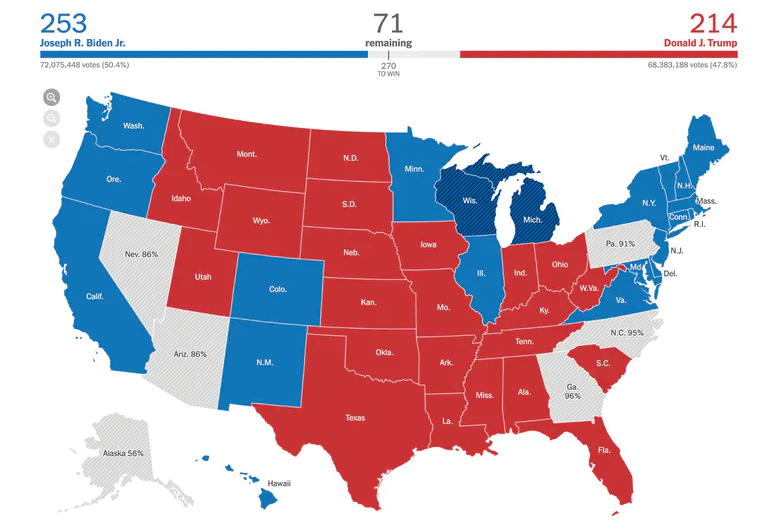

If one is to look at this map from The New York Times that uses colors based on the final result of the vote:

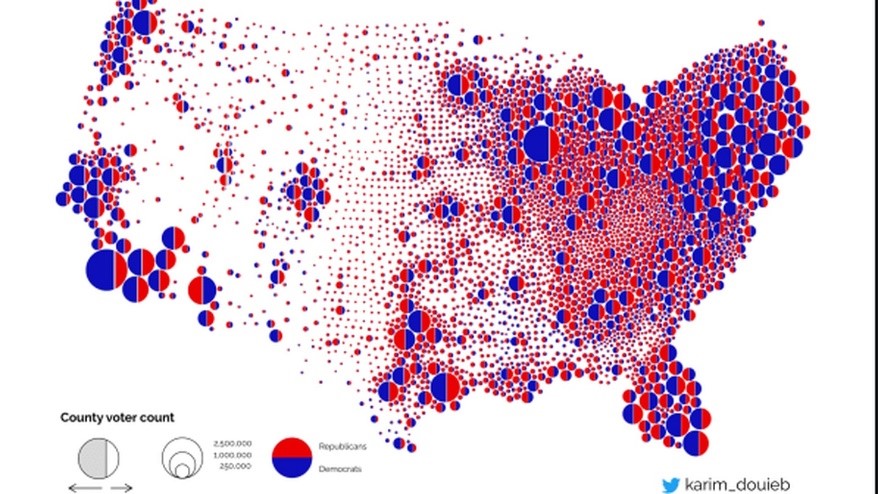

…and then, on this one made by a Belgian data analyst, Karim Douieb showing voting data adjusted with population data…

… he or she could rightfully ask the question, which one shows The Truth.

Of course, the answer is „both”. The first one is correct, too, but so is the second one.

They just use different visualization methods to depict the results.

On the other hand, the second map shows much better what the US currently is. And I admit that this statement is not „groundbreaking”, but…

There is no “blue tidal wave” or “sea of red”, despite some maps showing that. The US, as a whole, is neither predominantly Republican, nor Democrat. It is a deeply divided country. With 74.5 million votes going to one candidate and 70,3 million to the other, one can hardly call that a smashing victory.

Even if big cities (look at California, or even Florida) are “bluer”, each and every one of them has a conservative base, too. And even if Republicans can easily win a county in the heart of the US, it is so sparsely populated that it looks like a teeny-tiny dot on the second map, and even there live some, who vote Democrat.

The fact is that no matter, who will actually emerge as a winner from the latest rounds of the Election Saga, almost half of the American population will not accept him. And every side can wave a map or a statistic to prove its right. (Not to mention the deluge of fake news.)

There are trends, though, that are easier to see on the first map (again, as they were already visible in 2016, 2012 or even before that): the South and the Midwest is Republican leaning, while the shores are (tendentially) more winnable for Democrats. This can be seen not only when it comes to presidential elections, but also when it comes to issues like the right to carry firearms, abortion, LGBTQ rights, climate change or taxes. It is always more unambiguous on state level. Except for the few swing states, most states are considered “safe” for one or the other party from election point of view.

Of course, this is a truth universally acknowledged. But knowing this is one thing. What to do with it is another.

Many (and not just devout Trump voters) fear that the next US President will be the weakest ever, with a Republican Senate, a House where the Democratic Party has the narrowest majority in 18 years, a conservative Supreme Court and 27 of 50 of governorships.

This was also acknowledged by Biden himself, who said that before naming some of his secretaries, first he wants to talk with Mitch McConnell to gauge whom Republicans would help confirm. (His announcement came around the same time when McConnell suggested that he may not even acknowledge Biden’s victory for several more weeks.)

All of the above point toward very difficult years to come in the US. At least as long as federal issues are concerned.

Biden promised to unite rather than divide the nation. And the whole world is watching what he’ll do at home, but also on international level. But he’ll likely succeed only if he finds issues that have bipartisan support and leaves the ideologically charged or disputed ones to lower levels, like for the states.

This might sound as a heresy, but in fact it used to be more of a rule than the exception for most of the history of the US: the federal level gained more and more importance only in the 20th century.

For example, defense, migration, foreign policy or international trade are issues that truly necessitate the federal government, and these topics have bipartisan support in most cases, like taking steps against China and Russia or supporting Israel, even if there are differences in the details. Getting ideologically charged issues out of the equation could also provide more flexibility in negotiations both at home and abroad. Whether he likes it or not, Biden might need to resort to the “live and let live” principle if he wants to be a successful president.