Now, that COVID-19 occupies only about half of the front page, the EU has finally time to focus on a very Hamletian dilemma: To China or not to China, that is the question.

With the US-China relations in a downward spiral (threatening the very existence of WHO, among others), the EU has to decide whether to get in line with the not-so-predictable and isolationist US foreign policy or to define its own relations with the Red Dragon. And if the latter, how exactly that relationship should look like.

Thus, Germany just unveiled the new logo (a Möbius strip, a symbol of unity and connectedness), the new Trumpian motto (“Gemeinsam. Europa wieder stark Machen.”, literally “Together. To make Europe strong again”, yet the official English version is decidedly different.) and the new website of the upcoming German EU Presidency, while Chancellor Merkel and Foreign Minister Heiko Maas mentioned a few of their priorities. With China being very high on the list.

Not as if they had just recently discovered the importance to China: the first ever 27+1 EU-China summit in Leipzig is already scheduled (and recently postponed), where a new investment agreement was to be signed, besides serious talks on environmental protection, providing the legacy Angela Merkel strives for. According to the Chancellor, the most important aspect of this would be the “strengthening Europe as an anchor of stability in the world”. She also said that a strong European approach towards China was desirable, because Beijing is determined to claim “a leading place in the existing structures of international architecture”. (And because the US is literally inviting it by voluntarily emptying the international field.)

Josep Borrell also demanded a “more robust strategy” against China on May 25th, but it is yet to be seen, how much the German and the EU ideas overlap. In another interview, Borrell claimed that Europe “had been naïve in its dealings with China” and “China has a different understanding of the international order.” He also said that the new approach should be more like “sensible containment” than “engagement”.

Now, as Heiko Maas put it, “the best way to influence China is to make it clear that the European Union is very united… and that it will not be possible to break individual countries out of this unity.”

The problem with this is that unity is scarce nowadays within the EU. In fact, as of now, there are no signs of it at all.

The EU had difficulties in the past to show unified position in foreign policy issues, especially when it came to dealing with giants like China. Interests diverge considerably when it comes to condemning China’s behavior on its own territory, with its own population, but also when it comes to Chinese investments or technology (think Huawei and its role in the development of 5G networks or the sale of a high tech German firm only halted by vehement US opposition).

This itself could prove challenging, but the double crisis attached (COVID-19 and US-China tensions escalating) forces the EU to answer a few questions, bust a few myths, accept some realities and learn from some mistakes, if it is to come to a unified position.

So, I’ll divide this analysis into two parts. The first will deal with some myths or preconceptions about the EU-China trade, while the second will delve deeper into the political field, examining the US-EU-China triangle.

The truth about China-EU trade relations

2016 was the year (at least according to the Mercator Institute for China Studies) when Chinese FDI in Europe peaked at 37,3 billion euros. The total value has started to drop in that year, both due to shifts inside China (Beijing imposing restrictions on irrational capital outflaws) and in the EU. In 2018 it was 18 billion euros, while in 2019 only 12 billion (that’s approximately the 2013 level). But still, in 2017, 71 percent of the 29,2 billion euro Chinese investment in Europe went to three countries: the UK, France and Germany.

There’s been a geographic shift lately: instead of the UK, Germany and France, Chinese investors now have their eyes on the North (the sale of Swedish giant Volvo was the first step in this direction and enabled Chinese carmakers to take a giant leap in terms of safety of their products.) In 2019, only 34,6 percent went to the above mentioned three countries, while Northern Europe received 53 percent. Eastern Europe is nowhere near the top, even if its share from Chinese FDI grew from 2 percent in 2018 to 3 percent in 2019. And remember, we’re talking about 10+ countries together.

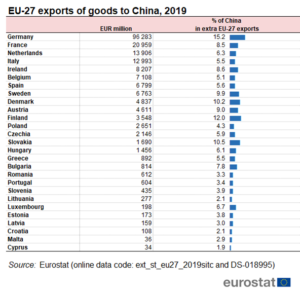

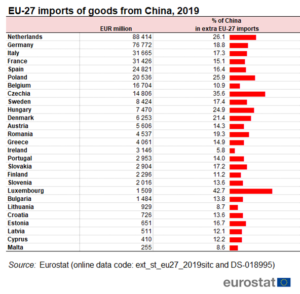

EU-China trade relations don’t look much different either: 78 percent of all European exports to China comes from Germany, the UK, France, Italy and the Netherlands, and vica versa, most European import from China arrives to the Netherlands, Germany, Italy and France. Two charts from Eurostat illustrate this brilliantly:

The economic giant of the EU, Germany has significant interests in China, as both the export and import charts show. Volkswagen sold 4,2 million cars to the country in 2019. In 2018, 45 percent of all EU exports to China came from Germany (that was 7,07 percent of all German exports) and that grew further in 2019, to 48 percent.

The Kuka scandal (a German robotics manufacturer) in 2016 was the wake up moment for many in Western Europe (not the growing crackdown on political dissidents in China). Months later another German sale (Aixtron) was blocked only because of the intervention of the Obama administration.

Now, in 2020 it seems obvious, of course, that China views its investments more than mere entry points to markets (or means of much needed knowledge and technology transfer): in Beijing’s eyes those are (and always have been) tools to influence policy too. And there is some truth in the words of those fearing that it might derail important European legislation: think about the case of an EU statement in 2017, when Greece blocked the decision just a few months after the Piraeus port was bought by a Chinese company.

Countries in Central and Eastern Europe have long been accused of selling themselves to China, with some claiming that China “eats” this region “one business deal at a time”, or, as Wess Mitchell (former director of CEPA and former US assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs) put it “the region is in bed with Beijing”. But if we look at the available data, it’ll reveal the staggering truth: CEE is NOT the most important European trading partner of China, nor the only region interested in cooperation and investments. Despite the fancy yearly 16+1 (17+1) meetings, during the last decade most Chinese investment went straight to Western Europe.

So it is hypocrisy from Western Europe to claim that only CEE or Southern countries are prone to be influenced by China or other foreign powers (remember that in 2014 the German government actually blocked the condemnation of Russia after the annexation of Crimea, mostly because of German natural gas imports from Russia). The German government has been also more muted lately as German sales to China are at risk. A recent EEAS report on Chinese disinformation campaign during the COVID-19 pandemic might also have been watered down to avoid loss of market for European companies. For some reason the EU ambassador to China allowed the Chinese MFA to censor the common article of 27 ambassadors on the occasion of the 45th anniversary of the establishment of European-Chinese diplomatic relations.

Business interests have for years overwritten policy considerations, despite clouds gathering on the horizon. Many analysts share the view that it was only after their investments turned less lucrative that German industrialists started to complain about the difficulties of doing business with China (like forced technology transfers, intellectual property theft and protectionism). In 2016 the level of European investments in China started to drop, alongside with growth levels or revenues, and so did the level of complacency. In 2017, Germany, France and Italy asked the Commission to look into an EU-wide investment screening mechanism. (Of course this was not the end of the story, but this topic could get another very lengthy article.) But even now, as China is seen more as a threat looming over Europe, and the voices urging a more strategic approach, many in Europe are still reluctant to confront Beijing, for fear of offsetting trade relations

With democracy in Hong Kong hanging on a thread, European companies are not worried about the human rights of people but fear for their investments and how the changing legal system of the city will affect their operation. Just a quick reminder: Hong Kong was the third most popular destination for EU FDI in 2017, even if much of this was chanelled to mainland China. There are currently 2,200 European companies operating in the city, for many of them it serves as their regional headquarters as well. The EU is Hong Kong’s second largest trading partner, with Germany being the largest among them (bilateral trade amounted to a staggering € 13,97 billion in 2019).

So far, I’ve covered the current state, ups and downs of Chinese-EU economic relations (one could always do a more detailed analysis, but I hope that was enough to make my point – if not, feel free to comment and demand more.)

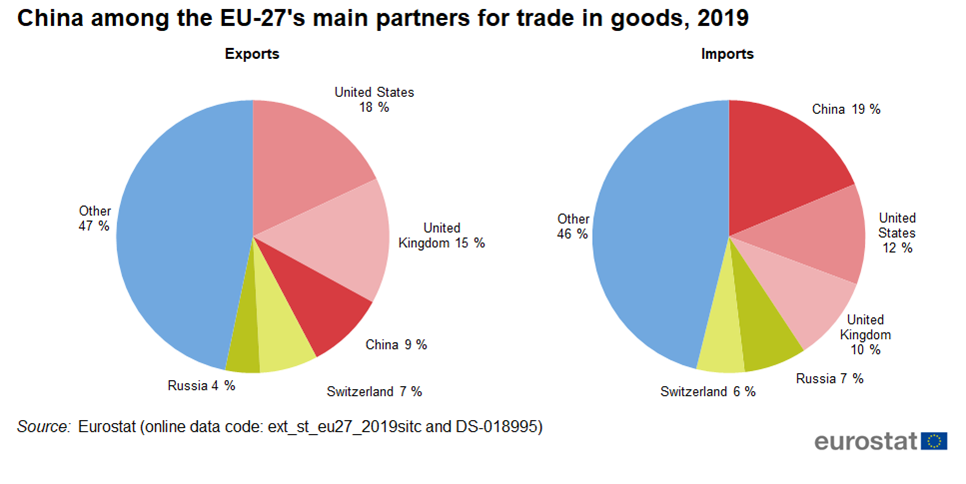

There are many, though who share another point of view that could be taken into account when deciding about the future of EU-Chinese relations. They claim that he greatest trading partner of the EU is of course … the EU. So, in their view, the importance of China as an export destination is slightly exaggerated. EU members trade nearly 30 billion euros a day with internal and extrernal partners, two-thirds of which takes place within the EU. With only 9 or so percent of all European exports going to China (approximately the same amount as to Switzerland), that could easily be offset by enhancing trade relations with other nations.

But the COVID-19 crisis has clearly shown the vulnerability of European supply chains: with 19 percent of the imports coming from China, diversification seems inevitable. And that might prove far more difficult (given the size of this).

Contrary to the common belief not only the smaller or economically weaker states are at risk of being blackmailed by China. Not a single nation in Europe is up to the challenge alone.

Coming up next: Politics