The West showed an unprecedented united front when presented with the ugly realities of war in Ukraine, and not just in standing together and condemning the events, lighting their famous landmark in the famed blue-yellow of the Ukrainian flag. A never-before seen list of sanctions, restrictions and prohibitions were followed by aid, both military and humanitarian, measurable in billions of dollars.

In various wordings, but every European political leader has repeated what President Biden said, when he declared that the war wasn’t only about Ukraine and Russia, but about “standing for what we believe in, for the future that we want for our world, for liberty, the right of countless countries to choose their own destiny, and the right of people to determine their own futures, or the principle that a country can’t change its neighbor’s borders by force. If we do not stand for freedom where it is at risk today, we’ll surely pay a steeper price tomorrow.”

While some, probably among them President Putin, have found it astonishing that 30+ countries managed to achieve that level of unanimity, others, like President Volodymyr Zelenskiy, might find it not enough.

Being way closer to the frontline, the NATO members on the eastern flank, from the Baltic States to Romania, would often prefer a more belligerent approach, and triy to push the Allies in that direction (like Poland with repeatedly offering to transfer its MiG-29 to Ukraine through an American airbase in Germany); while others, especially those who share(d) strong economic ties with Moscow would have wanted to minimalize the backlash.

This is more than true to Germany, that, due to a variety of historical and economic factors tried to stay back or out of the conflict, at least until Russia hadn’t started its “special operation”; even if it meant repeated criticism from Berlin’s allies.

While Washington … Washington is enjoying all the benefits of that big blue blot on the surface of the globe called the Atlantic Ocean. The U.S. is also suffering the effects of the sanctions, but with different interests and definitely and significantly less interdependence with Russia, Washington’s willingness to take risks is different.

On the level of the population, the difference is significant-to-none.

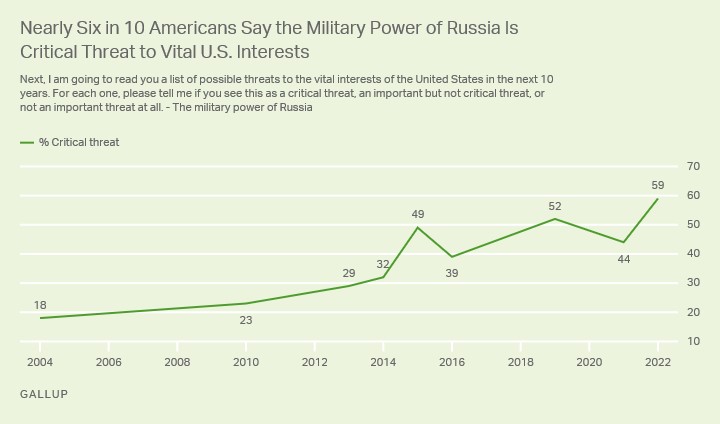

Ask people either in the US or in Germany the answer is the same: Russian military power is seen as a threat; or, based on a Gallup survey from February, a critical threat to US vital interests to 59 percent of the respondents, irrespective of political affiliation. In fact, Republicans and Democrats are united in their negative views of the Russian Bear, with an overwhelming majority (88 percent) within both groups holding a very unfavorable view of the country.

This is true, even if, leading up to the invasion, 57 percent said that the US should not send troops to Ukraine and only 54 percent agreed with deploying more soldiers to the eastern flanks of NATO (Quinnipiac University Poll). Another poll (AP-NORC) found that about 72 percent of Americans thought that their country should play a minimal role in the conflict.

Similar numbers were shown in various polls across Germany.

But on political/strategic/military level, there are some differences, due to a series of underlying factors and they seem to diminish with time as Germany started the greatest military development program it has seen since WWII. Even before the first round of sanctions was announced, it was considered likely that “it would hit Europe the most and the U.S. the least”, the way one German Green Bundestag representative put it.

There are similarities, too, just like President Biden made it clear that the Americans are not willing to fight, Germany isn’t ready to send in troops, either. In fact, the US has actually pulled out all troops from the country who were serving there as military advisers and monitors days before the invasion. Interventionism is off the table both in Berlin and in Washington; not even well-known hawks (think Republican Senator Ted Cruz) want the president to put American boots on Ukrainian soil and “start a shooting war with Putin”. Steps were taken though, to send more troops (or redeploy those already in Europe) to the eastern flank, to bolster NATO allies that border Ukraine and Russia.

But in the weeks leading up to the conflict, despite being one of the world’s biggest arms exporters, Germany was rather reluctant to actively assist Ukraine, refusing to send military hardware, except for protective helmets and alike, trying to stick to their policy of not sending lethal weapons to crisis regions. That earned some bad publicity for Berlin, with Kyiv’s Mayor Vitali Klitschko joking to German newspaper BILD Daily, “What will Germany send next? Pillows?”

Opinion polls all through the country had supported the non-interventionist standpoint, allowing Chancellor Olaf Scholz to declare, “My duty is to do what is in the interests of the German people and what in this case is the point of view of our citizens.”

Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock stated similar things, emphasizing that Germany was a financial donor to Ukraine and stating that “I don’t think it is realistic to believe such weapons exports could turn around the military imbalance. The best protection is to prevent further aggression. The strongest weapon (…) is that we (…) make clear every new aggression will have massive consequences.”

Well, she was at least right on that.

The aggression led to a complete U-turn in German foreign and defense policy, to German weapons being shipped to Ukraine. It is yet to be seen, what role German soldiers will play in an eventual peacekeeping mission in Ukraine (if it would ever materialize).

On the economic front, it is too early to predict the exact impact of the invasion and the sanctions, the increase in energy prices and the prices of basic commodities is obvious. It’s also a no-brainer that the level of economic uncertainty is to rise all over the world, affecting both households and firms negatively.

Once again, the effects will be felt more in Europe (and in all the countries of Asia and Africa that are the primary buyers of Russian and Ukrainian wheat, as the two together produce about 30 percent of global wheat exports, while Ukraine alone about 15 percent of global corn exports) than in America, as the U.S. imports relatively little directly from Russia. Americans, too will likely feel the change but more likely only as the knock-on effects, that drive (at least temporarily) prices up on basically any market, from raw materials to finished goods.

Oil, gas, wheat (and maybe sunflower oil) had been in the center of attention, but as Ukraine is also a globally significant producer of uranium, titanium, iron ore, steel and ammonia, many other sectors will also feel the burden.

The Nord Stream II pipeline, subject to a lot of criticism even before the Russian invasion, became one of the first major casualties of the conflict. With Germany’s reliance on gas being very high (and having been rising), the cost of replacing Russian gas will be even higher.

Just like every other country, Germany has started to search for alternatives. The latest of such steps came on March 20, when German Economy and Climate Minister Robert Habeck visited Qatar to “negotiate a long-term energy partnership”, also discussing other ways to enhance bilateral relations. Companies in Qatar must be celebrating, as (according to the official statement) Qatar had sought for years to supply Germany, but discussions never led to concrete agreements. And of course, first Germany needs to build the necessary infrastructure, like the two planned LNG terminals. Without those, currently Germany cannot receive direct shipments of LNG.

While Washington, with America’s less dependence on Russian oil and natural gas (and having quickly found alternatives, like starting to make friends with Venezuela again), had an easier time to ban those products, that step would deliver a serious blow to German economy, already under immense pressure due to the combined effects of the other sanctions and high energy prices.

Every new round of sanctions is likely to test the unity of the EU’s 27 members and might lead to fractures in the wall.