In the year 1789, something new and inspiring began.

On July 14, the Bastille, the notorious prison in the outskirts of Paris was stormed by the angry crowd, signaling the beginning of the end of the French monarchy. Seeking to dismantle the oppressive monarchy, feudal privileges and social hierarchies, the enthusiastic revolutionaries replaced the golden fleurs-de-lis with the Tricolore, and chanted gleefully about Liberté, Egalité and Fraternité.

While the French Revolution surely brought along much welcomed and long-lasting changes, pretty soon, “just like Saturn, the Revolution devoured its children”. The happy chanting was displaced by the screams of the executed (lynched) during La Terreur, then by the clash of weapons all over Europe during the Napoleonic Wars.

Even sans the plans to conquer the whole continent, if one is only looking at the home-front, Bonaparte Napoleon’s dictatorship (empire) was almost farther away from the original revolutionary ideas than the Ancien Régime itself.

It isn’t just the French Revolution that, during the process of its development, deviated from the original lofty ideas and evolved into something completely different. A more recent example is Karl Marx’s noble dream about working-class revolution and about lifting the poor, that turned into several decades of authoritarian regimes, suppression of dissent and mass suffering.

Apparently, the same fate befell to the green movements.

Green politics began to take shape in the 1970s, when the notions of environmentalism, non-violence, social justice and grassroots democracy gained wider acceptance. Striving for a sustainable future and environmental consciousness, ideas very easy to identify with, green movements spread from the Western world all around the globe.

Five decades later, the “Greens” of today bear not much resemblance to their predecessors.

Not only by demanding “eco-hegemony” (thus, a “complete regime change” by “broadening its base so the political support becomes hegemonic across the whole society … complete control over the minds of the voters, ringing some bells, anyone?).

That is one (far-left) end of the “green spectrum”.

Hiding behind a “revolutionary” (because, obviously, cautious, step-by-step reforms are not enough) façade and screaming about “eco-apocalypse”, the pursue of “energy reset” is used to demand far-reaching societal changes that (more often than not) hurt the very people they claim to protect.

Just to bring one example, all over the world, people are struggling to pay their energy bills. A problem to which the solution (especially not on the short and medium term) is not renewable energy, given the technical limitations and the few decades still needed for the technology “to mature”. Just like that, as long as an average Briton (European) produces more carbon in two days than many in the developing world during a whole year, it is hypocrisy to demand that they are measured by the same standards.

So, on one end of the Green Spectrum there are the real revolutionary radicals.

Yes, it is a “Green spectrum”, because the Green movement of today is about as diverse as the LGBTQI+ movement. And its members don’t necessarily like each other or even agree with each other on the best action plan.

The other end are a set of politicians who, realizing that green policies captivate the hears and minds of people, yet fail to gather enough votes (not in the least due to the price tag attached), turned the original ideas into fancy charades they can hide behind and justify whatever policy they deem fit to grab power and hold onto it.

Thus could happen that, for example, in the U.K there are members of the Green Party who oppose solar farms. Or that, in the U.S., green transition threatens with even more loss of workers’ rights, forcing the administration to mix blatant lies with vague promises. Or that while on the campaign trail, German Greens were “coming for the car”, yet have since assisted in “greenwashing” the country’s car manufacturing industry and are still sitting in coalition with the Socialists and the Free Democrats.

Of course, there are always people who would want to stick to radical ideas. They have their own role in the Green Circus directed by politicians: addressing, satisfying and entertaining the far-end of the Green voter base.

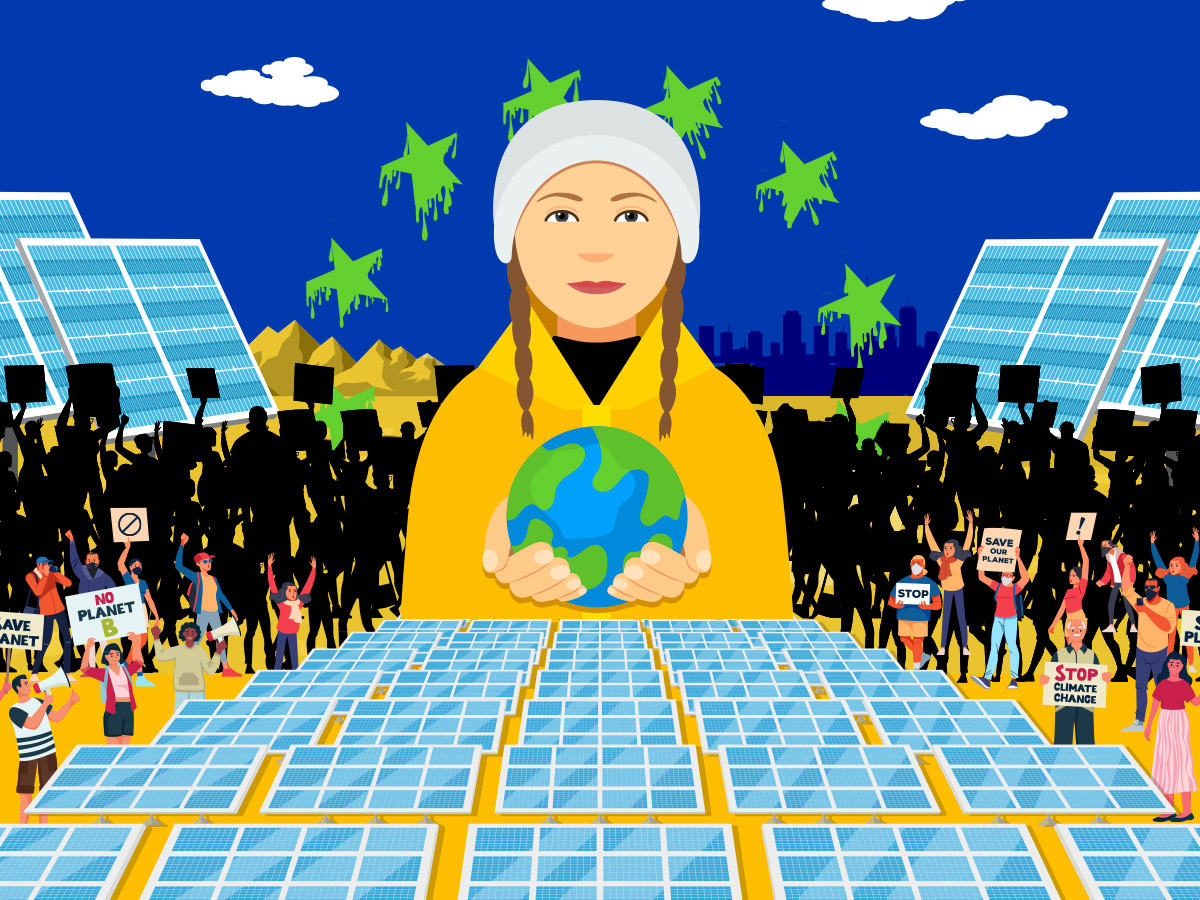

Take for example, Greta Thunberg.

One can like or dislike her. But the rise and fall of the poster child of climate activism is an example of Green hypocrisy. She was “the useful idiot” until Green movements needed her as an icon, a face for a carefully orchestrated PR campaign (hiding behind which is a PR guru called Ingmar Rentzhog). There was not a day her words or actions didn’t make it to the headlines.

Today, one would be excused to think that she died (save for her regular arrests).

Because she is too radical, the changes she demands are too draconian – because instead of “streamlining” her policies, making compromises or adapting them to fit whatever political goals they should, she refused to deviate from them. Her activity, or, for that matter, that of the other disruptive climate protesters (think: Extinction Rebellion), threaten with the loss of the sympathy of the very same (wider) supporter base the Greens are aiming for.

As this is not something a “Green” politician can admit without losing many voters, Greta was simply “forgotten” once she fulfilled her role. She is still out there, she is working, but one must search really hard to find her. She was replaced by a “next generation of climate and environmental campaigners”.

Politicians (with established voter base and connections) are more difficult “to forget” by their parties.

It looks like the European Parliament had become some sort of sanctuary for them (a great analysis about the discrepancy between the success of Green parties on the national and EU level was written by Naomi Tilles – Where the Grass is Greener: Comparing Green Party Success in National Parliamentary Elections and the 2019 European Parliamentary Election, pointing out that many Green parties across the continent gained more than twice the proportion of EP seats in 2019 compared to the previous national election).

A place where (far from the home front and more hidden from the average voter) they can represent their radical ideas. (And a place they can more easily get in, if Ms. Tilles is at least partially correct: according to her research, during national ballots, voters use “tactical voting” and are more inclined support a mainstream party, but follow a different voting pattern during EP elections. Green parties also emphasized different issues as in the national manifestos.)

Working with revolutionary zeal, they seemed to have forgotten that even the greenest countryside cannot make people forget some of their more pressing issues. And this forgetfulness might have actually alienated voters and might have helped to fuel the ever growing euro-skepticism in general, and belief in the value of green policies, in particular.

Something other politicians, like some in the EPP had noticed. As Peter Liese, German MEP put it, “sometimes we have overdone it … not giving people the choice, … but making very prescriptive decisions… when we do everything that the Greens want … we should take people along.”

Radical, irresponsible and not adequately prepared and researched proposals might actually hurt the Green cause in the long term. Like it happened with the latest vote (or rather, the absence of it) on the Nature Restoration Law that is opposed by Austria, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, Hungary, Poland and Sweden for a wide variety of reasons, not in the least due to the difficulties it would mean to the already struggling agricultural sector. (Another item, a proposal to halve pesticide use was already withdrawn due to lack of support.)

All it did was leading to hours long debates and mud-slinging, diverting scarce and valuable resources and attention from other, probably even more pressing issues.

Fast paced environmental legislation hurts more than just farmers. As President Macron put it last year, a pause would give time to industries to absorb recently-agreed laws, to see the results, to learn some lessons and to adapt if necessary. Joining him, Dutch Nature Minister Christianne van der Wal declared, “we cannot do everything everywhere – housing, energy transition, nature restoration, flood protection”.

While the American version of Green Transition is not without its contradictions and social setbacks, one thing stands out compared to the European versions so far on table. That is the difference in the chosen path. Washington managed to start a project with far-reaching consequences across many sectors, supporting private sector investment in renewable energy and sustainable technologies … all the European “Green Transition” offered until now was restrictions and cut backs.