It is finally out.

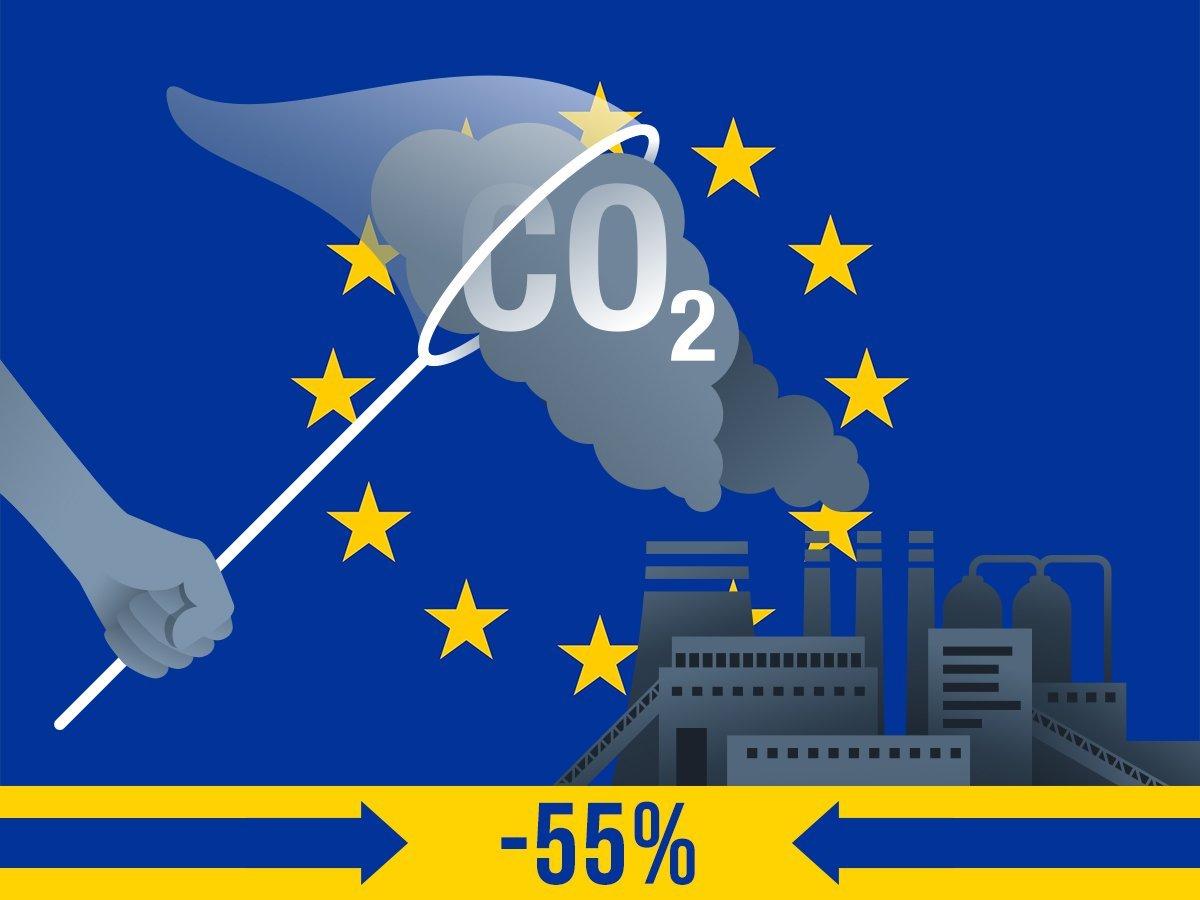

The European Commission recently published its “Fit for 55” program, intended to facilitate a cut in greenhouse gas emissions of 55 percent by 2030 compared to 1990 and on the long run, aiming to turn the EU into an emission-free zone. The document bears historical weight, making the block the first global power to turn those, sometimes vague goals into real-world policies. The hope is that “climate policy” will be more than a task of the executive, but instead will be part of the everyday lives of the average citizen.

A noble mission, no questions.

And an impressive package even if green groups have already criticized and condemned it, like the EU director of Greenpeace, Jorgo Riss, who said that “This package of measures from the Commission is a fireworks display over a rubbish dump. It may look impressive, but move in close and it begins to smell. To really make a difference, the EU and European governments need to stop the greenwashing and end support for fossil fuels, polluting transport, industrial farming and deforestation.”

If and when everything goes according to plans, the green transition of the continent results in a complete model-change, let it be about technology, economy or society. This, in turn, will give the EU an advantage in the competition among great powers. It would become, once again, a flagship for the world.

If and when something goes wrong, and well, ever since General Carl von Clausewitz we know that the “fog of war”’ hides about three-quarters of all the data needed to make informed decisions, so if that scenario happens, the “green transition” might push the competitiveness of the region back to the Middle Ages, figuratively speaking.

While most goals and ideas are realistic and probably beneficial, few of the proposals seem questionable, especially from social point of view. And more likely than not, would affect the Eastern (and poorer) part of the bloc differently than the better-off Western countries, like plans to impose fees on heating buildings, fees, well, taxes for carbon emissions caused by road transportation or revised CO2 emissions standards for new cars.

For example, emissions trading for buildings and road transport, while understandable from an environmental protectionist point of view, and even might result in significant decarbonization of the two sectors, which currently account for 22 percent and 35 percent of all EU emissions, respectively; is likely to further raise the costs of construction and in parallel, diminish the value of already existing buildings.

Though, in theory, the scheme’s impact on citizens aims to be indirect, in the end it will inevitably result in higher transportation prices and heating bills. If we translate it to CEE realities, it would mean punishing the already worse-off members of the society, who don’t have the financial means or the necessary knowledge to adapt to these changes, both when it comes to private citizens or SMEs. For example, in Romania, where, at least according to a 2018 report, 1 in 4 people live in a house without bath, shower or indoor flushing toilet, the problems of the average citizen are completely different from any other EU country. (Except maybe Lithuania, Bulgaria and Latvia.) Think of the Pyramid of Maslow.

And it is not only the CEE region where a hike in fuel prices might result in social unrest, it is enough to think about the gilets jaunes (yellow vests) movement in France. In a survey conducted by FOCUS in June 2021, only one-third of the interviewed German citizens said that they would support the new policies, aiming at emissions reductions, if those’d result in the rise of fuel prices. On 13 June, Swiss citizens also rejected a set of policies intended to fight climate change, clearly being worried about the impact on the economy, especially in light of the current COVID-19 crisis.

The proposed Social Climate Fund might or might not be able to balance these challenges, it will depend on many things, including whether the current proposal (that contributions to each country’s own social scheme should be conditional upon achieving pre-defined targets) gets accepted or not.

The same applies to another questionable measure in the package, to the push for electric and against “normal” vehicles. Setting aside the fact that the very notion of electric cars being eco-friendlier than combustion-energy cars is a debatable one, electric cars are more expensive both to produce and to use, once again “punishing” the poor. The proposal is based on the calculation that the average life-span of a car is 15 years, thus the complete conversion of the car parc would finish only in 2035 or beyond and by that time, electric cars would be affordable to all. In theory, it could work, but as in 2021 we’ve already seen, a minor hiccup (a global shortage of microchips) can cause stoppages, price rises and prolonged waiting times.

Oxfam drew attention to another inequality, this time regarding the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (known as CBAM) that aims to offset the negative effects of competitive disadvantage on EU business caused by decarbonization. Just like with the above measures, it is yet to be seen, how it would and could be implemented (e.g. where the data will come from, especially in case of countries with less than reliable statistical practices), as current proposals aim to account for both the carbon footprint of the goods imported and the implicit carbon price they face in five emission-intensive sectors, aluminium, steel, cement, fertilizer and electricity. Then there is the question, how the whole scheme will comply with current WTO regulations.

According to Oxfam’s European Head of Office, Evelien van Roemburg, “… (the) proposal for a carbon border tax burdens some of the world’s lowest income countries with a heavy tariff. The proposal also plans to channel these tax revenues into the EU budget rather than allocating them to the green transition. This is unfair and unjust.” The EU might deem it “it is not my business”, but those lower income countries also happen to be the greatest sources of migration. And that is EU business.

Oxfam also highlighted the fact, that even within the EU, the different strata of society contributed differently to carbon emissions, with the richest ten percent’s carbon footprint being significantly higher, in fact growing by 10 percent during the last three decades, than that of the poorer. Since 1990, emission cuts have been achieved only by latter.

But for the poor, energy is not a luxury item, but an everyday necessity, the additional fees/taxes on it having a direct result on those people’s standard of living. Heating is already a heavy burden, according to one estimate, in 2018, some 34 million Europeans were unable to keep their homes adequately warm. Energy poverty is not a future prospect, it is a very real present.

Again, the proposed social fund might compensate for this, but wouldn’t it be easier to avoid adding an extra bureaucratic step and finding a differentiated method to reaching the same goal?

“ Again, the proposed social fund might compensate for this, but wouldn’t it be easier to avoid adding an extra bureaucratic step and finding a differentiated method to reaching the same goal?” – well, what IS the “differentiated method”? Put it on the table so we, and others, can compare it with the system you so fervently criticize!? Without it your article only rises questions, but leaves the job half done. We must have options, but with well argued and documented details!