Europe stands united behind Ukraine and is, as of now willing to pay the price of this decision.

As many analysts have pointed already out, to make the sanctions bite, the world, especially the EU, had to hurt itself.

Until now, Europe has been the largest source of FDI into Russia, accounting to anything between 55 percent and 75 percent of the country’s FDI stock and Russia’s largest trading partner with a 37 percent share from Russia’s global trade.

Not only Germany (with 38 out of the 40 companies listed on the DAX having investments in Russia) or France (35 out of 40 on CAC), but almost all European countries looked at Russia as a good place to invest. It was only a month ago, that Vladimir Putin had a video call with about two dozen Italian top executives, to talk about strengthening economic ties.

After the fall of the Iron Curtain, hopes were high that the ever-deepening economic cooperation would eventually lead to peaceful coexistence, so security or “classical” geopolitical concerns were mainly overlooked in exchange for investments.

That is likely to change.

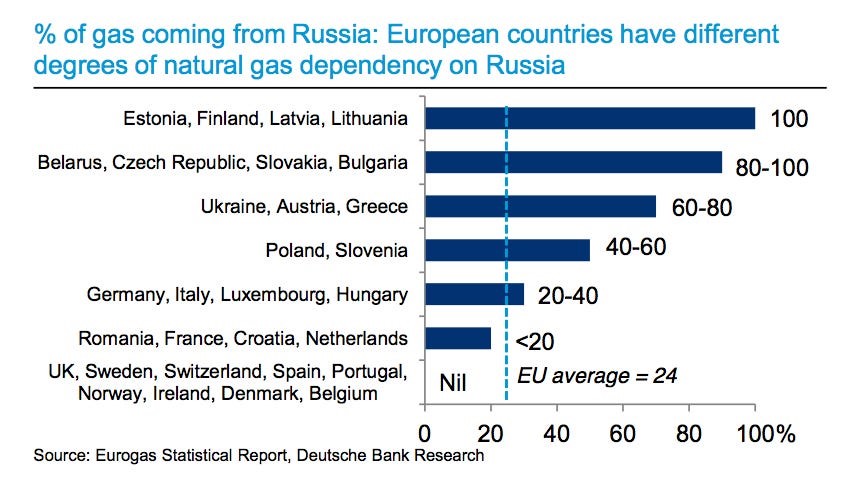

The short-term price for the shift came in the form of stock markets plunging, inflation soaring and already high energy prices climbing even higher. Of course, as Europe has a huge energy dependency problem, the energy price question seems to be probably the most pressing one, so it is not a coincidence that, with the exception of the halt on the already disputed Nord Stream II pipeline, the energy sector was mostly left out of the sanctions (it would be hit indirectly, of course).

But it is also a pressing issue for Russia, too, even if, as the supplier, it seems to have the upper hand in the question, because about 70 percent of Russian gas exports and half of its oil exports go to Europe, and it is rather unlikely that it can diversify its costumers or reach new ones quickly enough, despite Pakistan volunteering to buy some of the gas, and China maybe being ready to buy at least parts of the 700,000 barrels a day of crude oil.

Another already visible change is the flock of investors withdrawing from Russia.

The biggest among them is BP with a 19.75 percent share in Rosneft, a stake the company would quit, ruining 30 years of successful cooperation; despite Rosneft accounting for around half of BP’s oil and gas reserves and a third of its production. Danone, ExxonMobile, Mondelez, Siemens, Renault, Volkswagen, Mercedes and many others are likely to follow suit among growing pressure to do so, and so will, most likely than not, several banks.

The long term will depend how the conflict in Ukraine ends, how much Russia can “sell” the outcome as a victory or how much it is willing to change course.

It is very likely that it won’t be just the business and financial world whose attitude will change, security arrangements in Europe and around the globe will also see a significant transformation.

Here, too, many taboos have fallen and not just in Berlin, that has changed its long-standing opposition against exporting lethal weapons to conflict zones.

For the first time, the EU decided to use an off budget financial institute, to finance the purchase and delivery of weapons and other equipment to a country that was under attack. Though it seems unlikely that Ukraine would be allowed to join the EU in a fast-tracked process (or at all), it is possible that relations would change.

The conflict in Ukraine has clearly showed Europe’s strategic vulnerability.

Sitting between the hammer and the anvil, two great powers with conflicting interests (in fact, three, as the US-China debate, though currently less prominent topic, hasn’t miraculously resolved itself, either), Europe was not in the position to pursue its own way. Dialogue, long preferred by leaders across the continent, proved insufficient this time.

The sanctions, that will hurt Russia, will hurt the West, too, but in between the two of them, the EU in general, and the Eastern flank of Europe in particular, would suffer more than the US. (Not to mention Ukraine, that pays not only with money but with blood for the Moscow-Washington competition.)

It is difficult to say, whether it could have been avoided, or could have happened differently, would Europe look differently, but in a world, that seems to have turned back to the logic of power and realpolitik, it probably wouldn’t hurt if Europe would be stronger.

Calls for a stronger Europe are not new.

Though, more often than not, they didn’t come from Berlin (for a wide variety of historical and economic reasons), but from Paris.

President Macron has been saying for years, that the peace enjoyed in Europe could not be taken for granted. He argued that, facing “a Russia which is at our borders and has shown that it can be a threat, we need a Europe which defends itself better alone, without just depending on the United States”.

Was it a self-fulfilling prophecy? Hardly.

It is called realpolitik.

Emanuel Macron has repeatedly called for strategic autonomy, for “a European proposal that builds a new order of security and stability”, to be “shared” with the allies of Europe in the framework of NATO. In the wake of the Ukraine war, he reasoned for “the free choice for states to participate in organizations, alliances, security arrangements of their choice, the inviolability of borders, the territorial integrity of states, the rejection of spheres of influence”.

All the above based on the foundations laid down after WWII and the fall of the Iron Curtain, back then, 30 years ago, still in cooperation with Russia.

It’s not that he’s ever been a Putin-fan, like some German politicians (think Gerhard Schröder) are, but there seems to be a shift of opinion on his side, at least compared with his 2019 remark on the NATO being brain dead.

Given the current situation, maintaining the unity and cohesion of Europe seems a top priority for the next decade (or more) to come.

It is not that Europe should abandon NATO, or the US, for that matter, because it should not. But the EU should be strong enough to be able to stand up and protect its own interests. Has to have a vision about where it stands in the world and should not be relying excessively on an outside force to protect it from another outside force, let it be armed threat or an economic one.

“We cannot be consumed by our petty differences anymore. We will be united in our common interests … we are fighting for our right to live, to exist… ” These words weren’t said by President Macron, though could have been. (For those interested, it was (fake-)President Whitmore in the Hollywood blockbuster Independence Day.)

More than ever, the EU needs to examine itself, identify those issues and interests that really matter and stand united in defending those. At least until the time when there will be once again more place for ideology-driven foreign policy outreaches.